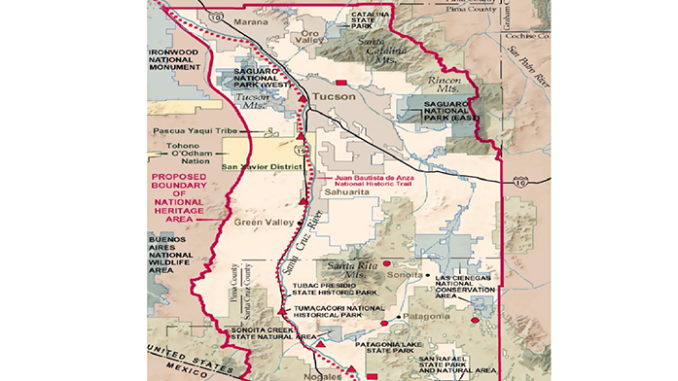

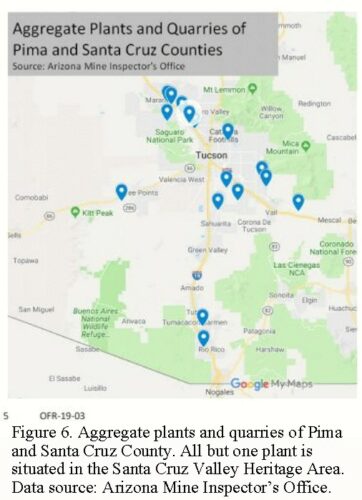

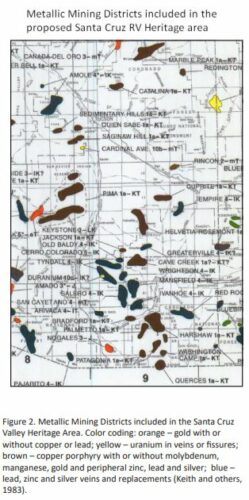

In March, 2019, President Trump signed legislation creating the 3,600 square mile Santa Cruz Valley National Heritage Area in parts of Pima and Santa Cruz Counties, Arizona. This has long been a pet project of Congressman Raul Grijalva. The proposed boundaries of the heritage area encompass major copper mines, sources of construction aggregate, and many ranches.

According to the Arizona Geological Survey, the mines in the area have produced 65 percent of the nation’s copper. (Maps in this article are from AZGS.) It remains to be seen whether establishment of an NHA will impact mining and mineral exploration.

The heritage area will be managed through the National Park Service which will contract management to a “local coordinating entity” which in this case is the Santa Cruz Valley Heritage Alliance. The Alliance will receive $1 million per year up to a maximum of $15 million for its services.

According to the House version of the legislation (link 3 below):

The purposes of this Act include:

(1) to establish the Santa Cruz Valley National Heritage Area in the State of Arizona;

(2) to implement the recommendations of the Alternative Concepts for Commemorating Spanish Colonization study completed by the National Park Service in 1991, and the Feasibility Study for the Santa Cruz Valley National Heritage Area prepared by the Center for Desert Archaeology in July 2005;

(3) to provide a management framework to foster a close working relationship with all levels of government, the private sector, and the local communities in the region and to conserve the region’s heritage while continuing to pursue compatible economic opportunities;

(4) to assist communities, organizations, and citizens in the State of Arizona in identifying, preserving, interpreting, and developing the historical, cultural, scenic, and natural resources of the region for the educational and inspirational benefit of current and future generations; and

(5) to provide appropriate linkages between units of the National Park System and communities, governments, and organizations within the National Heritage Area.

The Act also gives these reassurances:

Nothing in this Act:

(1) abridges the rights of any property owner (whether public or private), including the right to refrain from participating in any plan, project, program, or activity conducted within the National Heritage Area;

(2) requires any property owner to permit public access (including access by Federal, State, Tribal, or local agencies) to the property of the property owner, or to modify public access or use of property of the property owner under any other Federal, State, Tribal, or local law;

(3) alters any duly adopted land use regulation, approved land use plan, or other regulatory authority of any Federal, State, Tribal, or local agency, or conveys any land use or other regulatory authority to any local coordinating entity, including but not necessarily limited to development and management of energy, water, or water-related infrastructure;

(4) authorizes or implies the reservation or appropriation of water or water rights;

(5) diminishes the authority of the State to manage fish and wildlife, including the regulation of fishing and hunting within the National Heritage Area; or

(6) creates any liability, or affects any liability under any other law, of any private property owner with respect to any person injured on the private property.

That sounds good in theory, but experience with other National Heritage Areas is not so good.

The Heritage Foundation (link 5 below) opines:

There are three key reasons why Congress should not create any new NHAs and why existing NHAs should become financially independent of the federal government, as their enabling legislation requires.

1) NHAs divert NPS resources from core responsibilities. NPS advocates and staff have long complained about the limited resources that Congress provides in comparison to its extensive responsibilities. Both the Government Accountability Office (GAO) and the Congressional Research Service estimate that the cost of NPS’s maintenance back-log exceeds several billion dollars and is rising despite increased annual appropriations.

2) Federal costs for NHAs are increasing at a rapid rate.

3) NHAs threaten private property rights. On the surface, most of the legislation designating an NHA, and the subsequent management plans that guide them, include explicit provisions prohibiting the NPS or the management entity from using eminent domain to acquire property. They also prohibit the use of federal funds to acquire private property by way of a voluntary transaction with a willing seller.

Nonetheless, NHAs pose a threat to private property rights through the exercise of restrictive zoning that may severely limit the extent to which property owners can develop or use their property. Termed “regulatory takings,” such zoning abuses are the most common form of property rights abuse today. They are also the most pernicious because they do not require any compensation to owners whose property values are reduced by the new zoning. (Read full article for details.)

The American Policy Center (link 4 below) opines:

Specifically, what is a National Heritage Area? To put it bluntly, it is a pork barrel earmark that harms property rights and local governance. Let me explain why that is. Heritage Areas have boundaries. These are very definite boundaries, and they have very definite consequences for folks who reside within them. National historic significance, obviously, is a very arbitrary term; so anyone’s property can end up falling under those guidelines.

The managing entity sets up non-elected boards, councils and regional governments to oversee policy inside the Heritage Area.

In the mix of special interest groups you’re going to find all of the usual suspects: Environmental groups; planning groups; historic preservation groups; all with their own private agendas – all working behind the scenes, creating policy, hovering over the members of the non-elected boards (perhaps even assuring their own people make up the boards), and all collecting the Park Service funds to pressure local governments to install their agenda. In many cases, these groups actually form a compact with the Interior Department to determine the guidelines that make up the land use management plan and the boundaries of the Heritage Area itself.

Now, after the boundaries are drawn and after the management plan has been approved by the Park Service, the management entity and its special interest groups, are given the federal funds, typically a million dollars a year, or more, and told to spend that money getting the management plan enacted at the local level.

Here’s how they operate with those funds. They go to local boards and local legislators and they say, Congress just passed this Heritage Area. “You are within the boundaries. We have identified these properties as those we deem significant. We have identified these businesses that we deem insignificant and a harm to these properties and a harm to the Heritage Area. We don’t have the power to make laws but you do. And here is some federal money. Now use whatever tools, whatever laws, whatever regulatory procedures you already have to make this management plan come into fruition.”

This sweeping mandate ensures that virtually every square inch of land within the boundaries is subject to the scrutiny of Park Service bureaucrats and their managing partners. That is the way it works. It’s done behind the scenes – out of the way of public input.

True private property ownership lies in one’s ability to do with his property as he wishes. Zoning and land-use policies are local decisions that have traditionally been the purview of locally elected officials who are directly accountable to the citizens that they represent.

But National Heritage Areas corrupt this inherently local process by adding federal dollars, federal mandates, and federal oversight to the mix. Along with an army of special interest carpet baggers who call themselves Stake Holders. (See the article for much more.)

References:

1) P.A. Pearthree and F.M. Conway, 2019, Preliminary evaluation of mineral resources

of the Santa Cruz Valley National Heritage Area, Arizona, Arizona Geological Survey, Open-file Report OFR-19-03 (link)

2) Southwestern Minerals Exploration Association (SMEA), 2001, Mineral Potential of Eastern Pima County, Arizona, Arizona Geological Survey Contributed Report 01-B (link) (Note: I am one of the co-authors of this report.)

3) Text of House version of establishing legislation: H.R. 6522 (115th): Santa Cruz Valley National Heritage Area Act (link)

4) Tom DeWeese, American Policy Center, 2012, National Heritage Areas: the Land Grabs Continue (link)

5) Cheryl Chumley and Ronald Utt, 2007, National Heritage Areas: Costly Economic Development Schemes that Threaten Property Rights, The Heritage Foundation (link)

Note to readers:

Visit my blog at: https://wryheat.wordpress.com/

Index with links to all my ADI articles: http://wp.me/P3SUNp-1pi

My comprehensive 30-page essay on climate change: http://wp.me/P3SUNp-1bq

A shorter ADI version is at https://arizonadailyindependent.com/2013/08/01/climate-change-in-perspective/