With the controversy today about immigration, it might be worth remembering that, on this date 101 years ago, mine owners, law enforcement and deputized vigilantes rounded up and “deported” some 1200 copper miners from Bisbee, Arizona, to the New Mexico desert. Most were immigrant strikers of many nationalities. They, along with native-born Americans, were herded into cattle cars at gun point. Children were separated from their parents. Their crime? Withholding their labor because the bosses would not give them safe working conditions, and because they wanted to be paid in American money instead of company scrip redeemable only at the overpriced company store.

Copper camps and company towns were racially segregated, with white Americans working the best-paying jobs. The early Western Federation of Miners union excluded Mexicans, Italians, Chinese and others, but a wildcat strike led by Mexican and Italian miners protesting wage cuts at the Phelps Dodge Morenci mine in 1903 resulted in convictions of both groups for “rioting.” Some went to Yuma Territorial Prison, others were deported back to their native countries.

“Dark as a dungeon” was how miners described their workplace in the 2,500 miles of tunnels that lie below the surface of Bisbee’s hills. George Warren staked the first claim in 1877, but lost it gambling. San Francisco’s DeWitt Bisbee and his investors bought the claims in 1880 and the town, incorporated in 1902, was named for him although Bisbee never set foot there.

By 1910 Bisbee’s 25,000 residents came from 35 mostly-immigrant ethnic groups, and the Cochise County seat was relocated there from Tombstone. The Copper Queen and related mines produced eight billion pounds of copper, 102 million ounces of silver, 2.8 million ounces of gold, 30 million pounds of lead, and 371 million pounds of zinc before closing in 1975.

On June 27, 1917, Bisbee miners set aside racial and ethnic differences and went on strike for better safety conditions and for the right to be paid in full with American money without the company coupons redeemable only at the company store. The United States had entered World War I three months earlier and employers were using patriotism as an excuse to attack unions, especially the anti-capitalist Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) which led the strike. The IWW, popularly known as the Wobblies, declared in its constitution that, “The working class and the employing class have nothing in common!” Phelps Dodge management agreed.

Cochise County Sheriff Harry Wheeler and Phelps Dodge General Manager Walter Douglas secretly deputized and armed 2,200 men, dubbing them the Loyalty League. On July 12, 1917, Sheriff Wheeler issued a statement: “I have formed a sheriff’s posse of 1,200 men in Bisbee and 1,000 in Douglas, all loyal Americans, for the purpose of arresting, on charges of vagrancy, treason, and of being disturbers of the peace in Cochise County, all those strange men who have congregated here from other parts and sections for the purpose of harassing and intimidating all men who desire to pursue their daily toil…This is no labor trouble…but a direct attempt to embarrass and injure the government of the United States.”

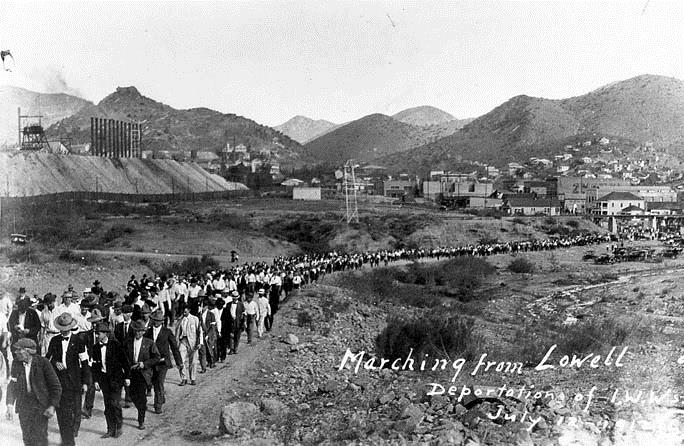

The Loyalty League, wearing white arm bands for identification, deployed into the Bisbee hills early on July 12, marching striking miners out of their homes at gunpoint. One IWW miner, James Brew, challenged the vigilantes and shot Loyalty Leaguer Orson McCrae dead before being himself gunned down.

Strikers were taken to a kangaroo court in a ball field. If they promised to return to work and were vouched for by a Loyalty Leaguer they were turned loose. Twelve hundred others were taken to cattle cars and box cars, locked in without food or water in summer temperatures of 112 degrees, and “deported” across the state line to New Mexico. The Bisbee Daily Review labeled the strikers “agitators, idlers, wreckers, traitors, spies and anarchists.”

Matt Hanhila, the seven-year-old child of immigrants from Finland, remembered that, “We were awakened by a loud knock on the door…I could see several men on our porch with rifles. They had come for my father.” Hanhila, who grew up to head Glendale Community College, watched his father, Felix, marched off and herded into a cattle car. His mother was forced to sell their home for whatever they could get to join her husband.

In the internment center Matt Hanhila became known as “the littlest striker.” When finally allowed to leave the camp, the family went to Minnesota where Felix worked in the iron mines, returning to Bisbee in 1920 to work under a false name, along with other re-named former deportees. More than one striker had escaped the roundup when their wives told Loyalty Leaguers that their husbands had died recently.

In Columbus, New Mexico, the deportees occupied an abandoned Mexican internment center under the watchful eyes of the U.S. Army while in Bisbee guards were posted on rooftops with rifles to keep strikers from returning. The largest ethnic group of deportees were Mexican (229), followed by American (167), Serbian (82), Finnish (76), Irish (67), Austrian (40), Croatian (35), British (32), Montenegran (24), German (20), Swedish (18) and Dalmatian (14). Twenty-three other nationalities had single-digit numbers. In the eyes of Phelps Dodge and Sheriff Harry Wheeler they were all illegal immigrant criminals.

IWW organizer Frank Little visited the camp, and then moved on to a strike in Butte, Montana, where he was lynched by six masked men. More than 13,000 workers attended Little’s funeral procession but no one was ever arrested for the crime. Phelps Dodge set a determined anti-union course and began funding election campaigns by friendly legislators to spread its influence. In 1983 company president Richard Moolick decided to “kill the union” and took a three-year strike to do it, aided by Governor Bruce Babbitt calling out the National Guard to protect strikebreakers.

A personal note: My maternal grandfather was an immigrant from Finland who worked in the copper mines around Butte, Montana. His name was Isaac Bjorklund. He joined the Wobblies, and participated in several strikes. In one strike there was dynamiting of the mines – employer violence against strikers was sometimes answered with striker violence against property – and Isaac rushed back to Finland. He returned a few years later with a wife and a shortened name, Lund, to work in the Baltimore steel industry. That probably made him an “illegal immigrant,” along with Felix Hanhila and most of the 1200 Bisbee “deportees,” and perhaps the ancestors of some of you reading this article. Something to think about.

And employers and their political cronies considered just about any strike “illegal,” as the #Red4Ed teachers are accused of today. Something else to think about.

Note: A new independent movie, Bisbee ’17, is currently making the rounds of film festivals and is expected to open commercially in September.

(Albert will be performing his “Bisbee Deportation Blues,” a mix of song and story, on Thursday, July 12, sometime between 6 and 8:30 p.m. at the weekly Hummin’ & Strummin’ gathering of local musicians and singers: Picture Rocks Community Center, 5615 N. Sanders Road. Free, all welcome.)

Photos: University of Arizona Library.