Local news outlets in Tucson recently announced the good news that medical equipment company Becton Dickinson is opening a facility in Tucson. That’s much better news for the economy than the opening of another low-wage restaurant or warehouse.

The company says that the facility, which will employ about 40 skilled people, is for the final assembly and sterilization of equipment. It has 90 similar facilities across the country.

Here’s the rest of the story and an angle you won’t get anywhere else about the thinking of the executives of big corporations, especially how they think about cities like Tucson.

The particular division of Becton Dickinson has its Arizona headquarters in Tempe, not in Tucson. And the company is headquartered in Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, not in Tucson. The company has 75,000 employees worldwide.

Having lived for ten years in northern New Jersey, which is part of metro New York City, I know the Garden State very well, including the good, the bad, and the ugly. Scores of big companies are headquartered there.

For instance, my wife worked at the headquarters of Warner Lambert, and I worked at the headquarters of the U.S. confectionery business of Mars, Inc. Our last home in the state was on the poorer side of a quaint town where AT&T was headquartered.

Not to virtue signal—because I’m not very virtuous—but I was also an activist who was honored as “Community Service Volunteer of the Year” on the Sunday front page of a major daily.

Tucson and similar cities are generally not locales that big corporations select for their headquarters, in spite of their rhetoric about diversity, social justice and giving back to the community, whatever that last bromide means.

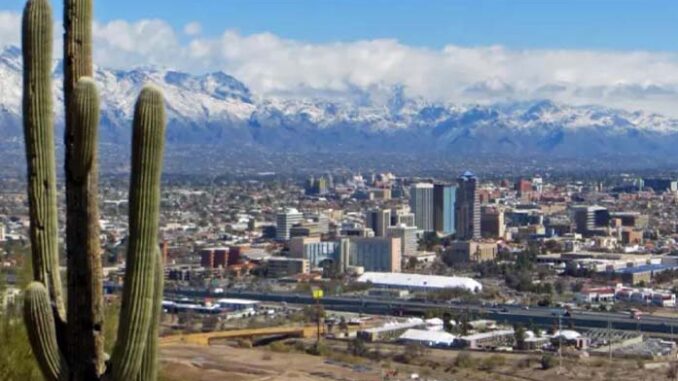

To that point, below are selected comparisons between the City of Tucson and Franklin Lakes, where Becton Dickinson is headquartered.

| Tucson | Franklin Lakes | |

| Median Household Income | $48,058 | $188,272 |

| Poverty Rate | 19.8% | 2.2% |

| Adults with College Degree | 28.9% | 75.4% |

| Non-Hispanic Whites | 42.6% | 78.5% |

| Chance of Being a Crime Victim | 1 in 204 | 1 in 5,491 |

Franklin Lakes is the kind of town preferred by executives of big corporations: low crime, excellent schools, plenty of amenities, high income, beautifully maintained, and mostly White. Corporate bigwigs are fine with putting subsidiary operations and back offices in towns that are more diverse and poor, but they want their headquarters to be in a town like Franklin Lakes, because that’s where they live.

Alternatively, if that’s not possible, they want their headquarters to be an easy commute from their home in an upscale town. In my boyhood home of St. Louis, for example, many of the executives of Emerson Electric, Wells Fargo Advisors, Anheuser Busch and other big companies headquartered in the city live a short commute away in the leafy suburb of Ladue, where the median household income is over $250,000. In New York City, executives gravitate to certain neighborhoods, streets, and apartment towers.

The Foothills section of metro Tucson is considered wealthy by Tucson standards, although its median household income is half that of Franklin Lakes. Tellingly, in the roughly 30 square miles of the Foothills, due to being an unincorporated and amorphous blob, there is not one public park, civic center, town center, or ball field, except for ball fields at public schools.

A corporate headquarters can be a game-changer for a city. That was the case when the Greyhound Corporation moved its headquarters and the headquarters of some of its subsidiary companies to Phoenix a half-century ago. Similarly, the homegrown company of Dell Computer was a catalyst for Austin becoming a tech center.

In the same vein, a recent Wall Street Journal story detailed the dramatic changes in the quality of life in northwest Arkansas, due to the area being the home for the headquarters of Walmart, Hunt Trucking, and Tyson Foods. These companies have funded cultural attractions, parks, bike/walk paths, and other amenities. In turn, these improvements have become a draw for people from other parts of the country who want a better standard of living and pretty neighborhoods. At the same time, the poor have benefited from higher wages and from local government having more tax revenue to invest in schools and social programs.