By Audrey Hernandez

He remembers that frigid stormy night in 1952 in Fresno, California. His mother clutched his baby brother and held his hand as they escaped a violent home. Jesus Hernandez was 4. He was terrified and confused.

His mother, Isabel, searched for shelter and a place to sleep. She spotted a narrow crawl space underneath a staircase behind a building. It was dark, cold and damp, but for Isabel and her two boys, Jesus and Augustine, it was a safe place to sleep for the night.

Isabel crawled underneath the stairwell, prepared a tiny space for Augustine and then encouraged Jesus to crawl inside. They settled in for the night, alone and hungry. Isabel fed Jesus tortillas and beans that she managed to grab before she ran out of the apartment.

Jesus didn’t understand what was going on. He sat down, tired, he’d been walking for almost two hours. He wondered why they would sleep under a staircase that night and why his mother was crying.

The boy began crying too, but his sobs were muffled by the sound of rain, traffic and barking dogs.

That was one of the first obstacles Jesus Hernandez faced. There would be many more as he fought in Vietnam, became a pioneer Latino television newsman who broke into the closed English-language broadcasting industry in Phoenix, Los Angeles and Portland and now produces a Phoenix-based television show featuring veterans.

He got his strength from his young mother, who hid her kids beneath the stairway that night.

Isabel harvested vegetables in the California fields to provide for Jesus. For a while, when he was a baby, Hernandez was cared for by his grandmother and aunts in Juarez, Mexico.

One day, Hernandez said, his mother returned home and found her unbathed son, who already learned to walk, eating adobe from a wall. At that moment, she decided to bring Jesus with her to California.

Eventually the family moved to Phoenix. There they lived in a local barrio once called “El Campito” at Seventh Street and Buckeye Road. At the time, people of color were not allowed to live north of Van Buren Street in Phoenix.

Sixty-eight-years later, Hernandez is now 72 and once again lives in Phoenix.

“I am an overcomer, who was challenged by poverty, driven by a dream and overachieved the improbable. I achieved what a lot of people thought I wasn’t able to do,” said Hernandez

***

Jesus Hernandez is among the very first Latino journalists in Arizona to break through English language television. He started his career in 1973, during a time when racism was pervasive in Phoenix. In the segregated town, there were limited opportunities for Mexican-American citizens, who were referred to as “Mexicans.” (Hernandez self-identifies as “Chicano” while younger people tend to self-identify as “Latino,” “Latina” or “Latinx.”)

Alfredo Gutierrez, a Chicano activist who worked with Cesar Chavez organizing farmworkers and then went on to be a prominent state senator and community activist, recalls the anti-Latino 1970s media landscape in Phoenix. Gutierrez said it was “probably the most controversial decade in a very long time.”

He says it was clear that to be in a prominent position as a Latino in the ‘70s, meant Latinos were setting themselves up to be a constant target of deep seeded racial feelings against them. Since Hernandez was on television almost every night, Gutierrez says he took more than most.

Jesus Hernandez, he said, “was the subject of one hell of a lot of jokes.”

“And when I say jokes, I mean that they were racially intended insults that were masqueraded as jokes that often happen to anyone in a prominent position,” said Gutierrez.

“The Arizona Republic,” he said, “is just a faint memory of what the media used to be in the ‘70s. It was a major political influence in this state. It was very conservative and opinionated, always strongly stating that Latinos had to stay in their place. I was constantly attacked by the Republic.”

“Big giant men, black ties, wearing glasses at their typewriters with a cloud of smoke,” is how Anita Luera describes The Arizona Republic newsroom when she would walk through it during her lunch time when she worked part-time in high school, at the newspaper’s engraving department. Now the director of high school programs for the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism, Luera left the newspaper in 1973 and was a producer at KOOL TV from 1978 to 1985.

Luera met Hernandez when she started at KOOL-TV. She said he instantly took her under his wing. They were two of the three Latinos working in the KOOL-TV newsroom in the ‘70s.

She says Jesus was like a “big brother” to her. She looked up to him, and she recalls how they used to collaborate to report on Latino issues.

“He was a big influencer in helping me understand the awareness of who I was in a very powerful newsroom,” Luera said. “He helped me learn to use my voice as a Latina and cover stories with a different perspective.”

Tom Chauncey, now a media law attorney, the son of the former owner of KOOL-TV and a photographer and editor at the station while Hernandez was there, describes Hernandez as being a “steady and calm person with a good on-air presence.”

“His experience in the military gave him that kind of broader perspective. Everybody else was emotional about issues, he was always calm in his reporting,” Chauncey said.

Hernandez being a Latino and getting a position at CBS News in Los Angeles and KOOL-TV didn’t seem like a big deal to Chauncey at the time.

“To anyone if you got a job in a major television station it was a big deal, it didn’t matter if you were black, brown or white,” Chauncey said.

***

Jesus Jose Hernandez is the oldest of three brothers, Augustine and Francisco. He was born in El Paso, Texas a border town separated from Mexico by the Rio Grande.

Hernandez lived in El Campito, a local Phoenix barrio, from age 5 up until he was 18 when he left to serve in the army. Hernandez faced a lot of obstacles that many Hispanic youth faced. His 16-month-tour in the army during the Vietnam war, ended in 1969. When he returned from Vietnam he felt like he went right back to the place he started, with no idea of what he wanted to be and no one to help him figure it out. He knew he wanted a professional career and did not want a life of manual labor. He thought about becoming a broadcast journalist after hearing an ad on the radio, and turned to the Valley’s largest Latino nonprofit, Chicanos Por La Causa, for guidance. Thanks to an advisor at the nonprofit, Terri Cruz, he eventually got his foot in the door of KOOL-TV, by landing a job in the promotions department.

“I would have taken any job at that point,” Hernandez said.

He moved up into television production, and later was promoted to become a broadcast journalist.

“I remember telling my news director that I had no experience in broadcasting and him telling me ‘that’s not my problem, that’s your problem, if you want the job here it is,’” Hernandez said.

The opportunity Hernandez was waiting for had come but he had zero experience in the industry.

“I had to learn quick. When I first started the job, I watched ‘60 Minutes’ religiously. They were always producing wonderful packages in their stories.” Hernandez said. “I used the skills I saw on television, in my own work and it helped after all.”

He was one of the first reporters to pronounce his name and other Latino’s names with a Spanish pronunciation.

“I decided to really use my god given name, people really liked the way I rolled my ‘r’s’”

He had to take voice articulation classes when he attended Phoenix College and remembers some instructors told him remarks like, “you’re never going to make it” and “you’re Hispanic so don’t even try.”

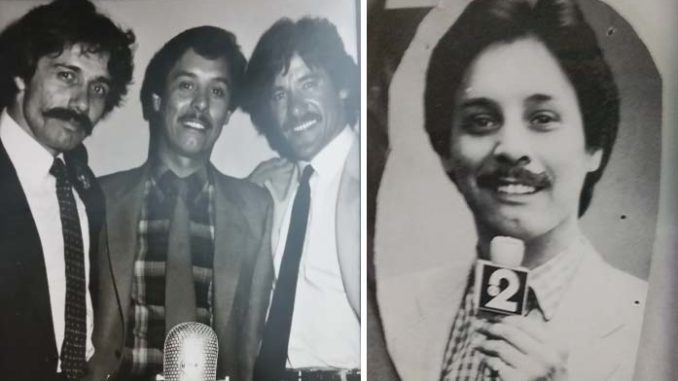

That reporting style at KOOL-TV garnered the attention of CBS News Channel 2 in Los Angeles where he spent five years there as a morning anchor and reporter. It was his second job in the industry, during a time when CBS Los Angeles was trying to get into the top 10 markets in the country.

“Getting it was a beautiful experience,” he said.

After Los Angeles, he worked for KOIN-TV, a CBS affiliate, in Portland, Oregon. In 1983 he returned home to Phoenix and went back to Channel 10. He also worked at the Spanish-language news outlet, Univision.

Hernandez hosted a PBS award-winning program ASU Research Review on Channel 8. He also produced and hosted “Living Today” a Phoenix Channel 11 program that garnered a Cable Ace award from the Academy of Cable Programming. Additionally, he produced and hosted “Latino AZ” a Hispanic themed television program featured on AZTV Channel 7 statewide.

Hernandez was also the marketing and communications manager at Friendly House, a non-profit that he said once taught his mother how to clean houses and find employment as a housekeeper.

“I wanted to give back to the organization that is now 100 years old and that helped my mother,” Hernandez explained.

Most recently he was a producer and reporter at Maricopa College Television. His work earned him a “Telly Award” for a segment featuring veterans at the colleges called “Pride in Service.”

Currently, Hernandez is the host, creator and executive producer of the Veterans Business Journey television program, in which he developed to honor veterans and because he is a Vietnam vet.

“Many of these veteran’s stories are never told. You enjoy your freedom and I enjoy your freedom because of veterans,” Hernandez said.

***

During the novel coronavirus, Hernandez works from home on the Veterans Business Journey project, writing other cultural stories and writing two books.

As he is now 72-years-old and a part of one of the high-risk groups of the virus, he says he cannot risk going out and making contact with those who might be infected.

He also worries for the “detrimental” impact this virus will have on small Latino businesses. “It will trigger a higher unemployment rate for Latinos and cause those businesses to fail,” Hernandez said. He mentions the lack of representation veterans have in the media and wishes the media would cover the high death rate among veterans.

As for Latino youth who are faced with similar challenges as him he says, “Never be less than that dream you have for yourself. Go for it and don’t let anyone tell you otherwise,” he said.