Once every November, as the sun sets in the west, it casts an especially warm glow across the El Capitan High School football field.

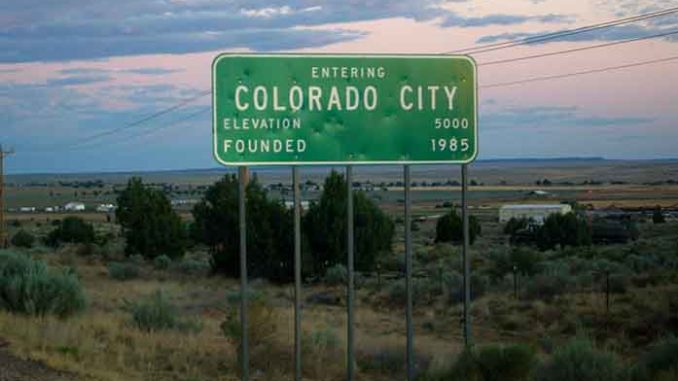

The residents of Colorado City, a town long known for its polygamist community and its notorious leader Warren Jeffs, gather en masse into the aging grandstands to watch the most popular sporting event of the year: the rivalry game between Arizona’s El Capitan Eagles and Utah’s Water Canyon High School Wildcats.

It’s a meeting that unites the border-straddling towns collectively known as Short Creek as kindred spirits. The game offers a chance for residents to escape the day’s challenges and bond over one of America’s favorite pastimes.

But when the sun set over the football field this November, the glow was muted as it swept over the barren seats.

El Capitan, a team that has made the Arizona 1A playoffs each of the last four years, had its season cut short because of a recent measles outbreak in Mohave County, one of the largest outbreaks in the country. Throughout the season, several players contracted the virus, ultimately forcing seven game cancellations, including El Capitan’s coveted matchup with their crosstown foes.

As this one-time Arizona polygamist community continues the work to reinvent itself following the conviction of Jeffs, its high school football team is caught in the crossfire of a health crisis, government skepticism and vaccine mistrust.

As of Monday, Arizona has reported 153 total cases of the measles, with 149 of those coming from Mohave County and the Short Creek area. The outbreak has forced many individuals to quarantine and, in the case of El Capitan, cancel sporting events.

For coach Stephen Campbell, the season has been nothing short of difficult, but in his eyes, therein lies the lesson.

“With hard times come hard people,” Campbell said. “And hard people, they get through hard times. With being down so many players, we came through and did the best we absolutely could.”

For a typical high school football team, losing a few players on a 40-to-70 player roster isn’t that disruptive. But for El Capitan, which plays in the Arizona Interscholastic Association’s eight-man 1A conference, the loss is substantial.

“Our last game was against Williams (High School), and we’re a 10-man team playing against a roster of 36 players,” Campbell said. “As you can imagine, our circumstances weren’t ideal.”

El Capitan lost its season finale to Williams 55-20, capping off a disappointing 0-4 record that stunted the progress the team had made over the last four seasons.

Within this tight-knit community, the losses from the measles outbreak have been felt by many. And though the season came to a disappointing conclusion, the resilience of El Capitan’s football team set an example for adapting to change and how sports can provide a blueprint for battling adversity.

‘A lot of growth’

Colorado City has experienced a multitude of changes in the past two decades. Just over a decade ago, the presence of sports bars and lottery machines against the town’s religious backdrop would have had locals in disbelief.

Today, the town hosts multiple bars, including its own brewery, as well as other modern fixations that have helped grow the community into a tourist destination not far from Zion National Park. In all, Colorado City has gone against the grain to embrace change as a positive force for the community.

But now, on the frontlines of the nation’s second largest measles outbreak, the town has fallen short of the one change necessary to stop it: vaccinations. With national attention surmounting, the call to action against the measles outbreak has been demanded, not applauded.

This is happening as the community continuously tries to separate itself from the conformist nature of the town’s history. Even now, a simple Google search of Colorado City will still show multiple results that reference Jeffs, the man largely responsible for the community’s fear of control.

Jeffs, the former leader of the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, was sentenced to life in prison in 2011 for the sexual assault of a a child under the age 14, along with an additional 20 years for sexual assault of another child under the age of 17.

Before his arrest, Jeffs ruled Colorado City with an iron fist. By banning books, practicing polygamy and forcing women and young girls to “keep sweet” –a core mantra of the church – in their arranged marriages, it gave Jeffs enough power to pose as the prophet he claimed to be.

Since Jeffs’ tyrannical rule ended, many of the community’s polygamists have relocated to small towns in other states including Texas, Utah and North Dakota. Most in Short Creek have embraced the community’s emancipation. As the town slowly becomes more receptive to control, residents such as Rebecca Bradshaw will attest that it isn’t as easy as people make it out to be, especially when it comes to conforming to government decisions on bodily autonomy.

“I almost think that it’s not a religious thing as much as it is a government thing, that they don’t want the government telling them what they can and can’t do,” Bradshaw said.

The Arizona Department of Health Services does not offer vaccination exemptions for distrust of the government, but it does offer exemptions for “personal beliefs,” such as religious reasons.

According to data from 2024, Cottonwood Elementary, Colorado City’s primary PK-5 school that feeds into El Capitan, only has 8% of its student body vaccinated against the measles virus, with 85% claiming a personal belief exemption.

The distrust of a controlling body, whether it is religious or governmental, has been a huge contributor to the measles outbreak. Before 2019, Mohave County had an overall kindergarten measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccination rate of 90.3%, slightly below the recommended 95% for herd immunity – yet still within reason.

But after COVID-19 swept the nation and government-mandated vaccinations diminished some people’s trust in them, the vaccination rate dropped to 78.4% by 2024, the lowest percentage of any county in Arizona.

Dr. Scott Steingard, a family practice physician with Optum-Arizona, voiced his concerns with the lack of vaccinations and urged the residents in measles hotspots like Colorado City to get their shots as soon as possible, regardless of religious or political affiliations.

“To me, the vaccine has proven effective to the point where, at one point, the CDC (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) said this was eradicated in the United States,” Steingard said. “So I think we have pretty good evidence that it works, it’s effective, it’s got virtually no side effects, it confers remarkable immunity for a lifetime and it’s proven safe.”

In the midst of the discord between outside control and vaccination efficacy, Bradshaw said the community has a strong connection to natural remedies, including the hosting of “measles parties,” large, coordinated gatherings of children in hopes that they contract the virus and develop natural immunity.

“They’ve said, ‘If we get exposed and we get it, we’re just living,’” Bradshaw said. “They just want to live and be normal.”

Steingard strongly opposes the idea of holding measles parties, citing their potential danger to at-risk children whose bodies are not prepared to take on the virus.

“They are playing with fire,” Steingard said. “You don’t know which child is going to be the one that their system is simply not ready for that type of viral load. Speaking as a parent, I wouldn’t want to be the parent that puts my child at that kind of a risk.”

At the end of the day, health decisions are determined by the families themselves. Like putting a bird back in its cage, it’s hard to relinquish personal choice and freedom after being without it for so long.

“I think they found out a lot of things on COVID-19, and it’s just when the government starts saying, ‘You have to do this’ and ‘mandatory this,’ people want to be free,” Bradshaw said. “That’s what America is about, is freedom.”

It’s the notion of freedom that unites the Short Creek community as the town shakes off its dark past to focus on a brighter future, a change that Bradshaw has had the privilege to witness firsthand.

“It’s changing for the better,” Bradshaw said. “In the last eight years, I’ve seen a lot of growth. It is going back to being more family-oriented, I would say, rather than religious-oriented.”

‘Enjoy every moment’

For Campbell, taking the job as football coach at El Capitan was a major adjustment. The transition from his 4A high school experience in nearby Hurricane, Utah, to a 1A high school that was only introduced as a part of the AIA 15 years before he arrived, was dramatic.

“I was just surprised by the tight-knit community they have,” Campbell said. “I was really impressed by everyone’s closeness.”

The bigger adjustment for Campbell was the shift from 11-man football to eight-man, a style of football that features different rules and strategies. Playing on an 80-yard field elicits a faster pace of play and higher scoring outcomes, even with the reduced amount of players on the lines.

But none of that would matter if Campbell couldn’t assemble a team. At the start of the 2025 season, the Eagles had just seven players rostered. But later, thanks to the coaching staff’s continuous enthusiasm toward building the team, the roster peaked at 16.

Riley Barlow, a junior center and defensive end, has seen the program evolve over the course of his three years at El Capitan. Despite the team’s lack of performance this season, Barlow believes in Campbell’s vision for the future and hopes the team can return to its winning ways.

“It’s been a struggle having new coaches every year,” Barlow said. “So now that we’re here with these guys, hopefully they can stay here and provide a better team and a better program.”

Barlow got his first taste of football his freshman year, when El Capitan had enough players to field a junior varsity team. Barlow now enters his senior year, and although his time on the football field is dwindling, he’s learned to not let that deter him from soaking up the fun and the experiences he’s had along the way.

“Enjoy every moment,” Barlow said. “You don’t know how long it’s going to last. At the beginning of the season, I didn’t even honestly think we’d have a football team. And I feel very rewarded to even have one this year.”

A moment full of enjoyment came last year when Barlow and his teammates suited up to play rival Water Canyon on its turf in Hildale. Though just seven minutes away, the differences between the two schools are night and day.

Because El Capitan and Water Canyon are on opposing sides of the state border, both schools receive different levels of funding. In Utah’s Hildale, the Wildcats have the luxury of a beautiful, state-of-the-art sports complex that includes baseball and softball fields.

But in Colorado City, the lack of funding has kept much of El Capitan’s athletics on one grassy field. Just north of the field lies a large, multi-million dollar sports complex in the process of construction, but its hollow interior is still years and millions of dollars short of completion.

Despite the divide, Barlow and El Capitan dominated Water Canyon 36-6 during last year’s rivalry matchup. For Barlow, the feeling of playing under the lights in a tense environment was nothing short of exhilarating.

“It’s electric,” Barlow said. “You run onto the field, the lights are peering down on you, you’ve got friends on the other side and you’re just ready to enjoy a great football game.”

The kinship between the two schools reflects the community’s values of unity and togetherness, and as it turns out, that’s a huge advantage for a team facing massive obstacles.

“Most of us have known each other for years,” Barlow said. “We’ve been playing football out here at lunch since junior high, and now we’re actually playing together. We know each other on that field. It’s like we’re almost connected in a way.”

It’s a connection that many folks in the area never had a chance to experience. Organized sports were among the activities banned while Jeffs was in control, which is ultimately a reason why the El Capitan Hawks and Water Canyon Wildcats are so heavily supported by locals.

Luke Merideth, who coaches the wrestling team at Water Canyon, knows firsthand the impact that sports has on the residents of Colorado City. Merideth has served the community, not just as a coach but as the co-executive director of the Short Creek Dream Center, an organization that helps house and uplift individuals facing life-changing trauma.

“I think that sports has brought the community together in a way that nothing else does,” Merideth said. “It’s a universal language.”

The Short Creek Dream Center, housed in the newly renovated former home of Jeffs, has helped the community get back on its feet following the fallout of the FLDS church scandal. It has renovated every bedroom of the 44-room facility, its website states, because “the house itself carried with it a lot of painful memories.” Merideth, who benefited from the Phoenix Dream Center himself after battling substance abuse, now has the chance to uplift those around him and help them overcome their obstacles.

“There have been some kids where I’ve identified with their struggle and found it to be a privilege to be part of their life and do that,” Merideth said. “It goes back to the way my coach helped me. My biggest moments are those particular ones where I feel like this is what I’m here for.”

Although the rivalry game with Water Canyon this year fell through the cracks, a collaboration between the two schools elicited a combined practice that united the two programs so that all was not lost because of the moments the teams missed during the measles outbreak.

“It was a great experience,” Campbell said. “We were doing our chants together, our prep-ups together and we enjoyed the competitive aspect of the sport, and that’s kind of the name of the game.”

For Barlow, representing the community on the field has been a privilege, and he recognizes how much it means to twin towns that share a controversial past.

“I think it’s really awesome that we have the opportunity to come and play football, because I know a lot of the adults around here didn’t get that chance,” Barlow said.

“So when they come out here to watch their kids come out and play and actually enjoy the game, it’s very uplifting and rewarding.”