The second week of Roger Wilson’s murder trial was only in session three days, but during that time jurors heard a witness being offered immunity for his testimony about drug activity, learned a key witness confessed during sex to being in the area of the shooting, and listened to testimony from a jailhouse “snitch.”

But the jurors did not hear about two motions made by defense attorney Chris Kimminau seeking to end the trial, including allegations that the Cochise County Attorney’s Office and Cochise County Sheriff’s Office withheld information about credibility issues involving one of the deputies who already testified.

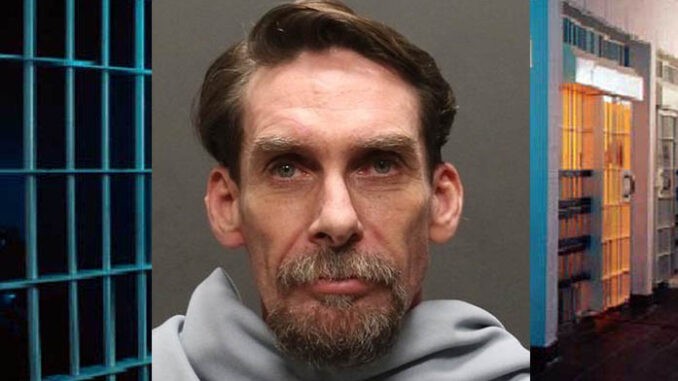

Wilson, 52, is charged with first-degree murder, second-degree murder, and manslaughter for his actions firing one round from a shotgun into the chest of Jose “JD” Arvizu, 22, shortly after 1 a.m. on June 22, 2017 outside the home of Wilson’s mother. His trial began Sept. 15 before Judge Timothy Dickerson of the Cochise County Superior Court.

Jurors were previously told by prosecution witnesses that the shotgun pellets hit Arvizu’s chest at a 45-degree downward trajectory and that the distance between Arvizu and Wilson was six to nine feet. They also heard testimony that Wilson is several inches taller than Arvizu.

Kimminau has consistently backed Wilson’s claimed self-defense for the shooting. One of Kimminau’s motions asked Dickerson to dismiss the charges against Wilson for lack of sufficient evidence put forth by prosecutor Lori Zucco.

The other motion was for a mistrial based on information Kimminau only learned at the end of week one. It dealt with a federal lawsuit filed earlier this year in Oregon involving Cochise County Sheriff Mark Dannels and one of his deputies who was among the first on scene after the shooting.

Dickerson denied both motions, but his rulings could be cited in any post-verdict appeal.

Investigators formally interviewed Wilson a few hours after the shooting. He told them he intended to protect himself and his mother, and their property, and not seriously hurt Arvizu. At the time of the interview Wilson did not know the young man had died.

Just days earlier, Arvizu and Wilson had a physical confrontation in front of witnesses during which Wilson’s nose was cut. Then less than one hour before the shooting the two had a verbal argument at the home of Robert Burton.

Jurors heard testimony in week one about the argument but last week they finally heard from Burton, who was subpoenaed to testify and could have been arrested if he failed to appear.

Burton made it clear he did not want to testify and frequently asked Dickerson whether he had to answer certain questions. At one point Zucco informed the judge she was granting Burton immunity, meaning he could not be prosecuted by local authorities for statements about specific incidents of drug activity.

Among his testimony, Burton told jurors he ordered Arvizu and Wilson to leave his property because of their hostilities. Wilson left immediately as instructed, Burton testified, but he had to tell Arvizu three times to leave.

Jurors heard Wilson’s taped statement to detectives in which he explained he ended up down the street at his mother’s home. He was trying to gain access to the gated yard in order to park the truck inside when he saw Arvizu walking in the roadway by the truck. Arvizu suddenly ran toward him, Wilson claimed.

“Roger had a split second to react” to Arvizu’s aggression, Kimminau told the jurors. He added that the law doesn’t require someone to wait to be attacked before acting in self-defense.

After being shot, Arvizu walked nearly 500 feet to the home of a friend. Wilson told detectives he was concerned about threats from other people which is why he attempted to reload the shotgun as he followed Arvizu down the street.

Someone at the friend’s house called 911 but Wilson did not contact anyone about the shooting for more than one hour. By then deputies were in the neighborhood tracking Arvizu’s blood drops down the road.

Deputies testified last week that Eric Lynn was found hiding under a bed in the residence Arvizu went to after being shot. Lynn was taken into custody for a warrant in a family court matter.

Lynn repeatedly denied having firsthand knowledge of the shooting, but he provided deputies with “helpful suggestions” about where to look for evidence. That made last week’s testimony by defense witness Hailey Johnson particularly important.

Johnson testified Lynn confessed to her during sex that he had in fact been present in the area of the shooting.

Deputies reportedly did not record their initial conversations with Wilson at the scene, even though they had been advised by a 911 dispatcher that reported shooting someone. They also did not record the initial conversation Lynn.

One of those deputies was Raymond McNeely, who is named along with Dannels and several other defendants in a recent federal wrongful arrest lawsuit from his time as a Coquille, Oregon police officer. Dannels at that time was the Coquille Police Chief.

RELATED ARTICE: Cochise Sheriff And Deputy Named In Oregon Lawsuit Prompts Question Of Who Pays For Expenses

Wilson also told deputies after the shooting that Arvizu and others were responsible for several thefts and burglaries in the area in 2016 to summer 2017. He deridingly referred to the group as the $5 Gangsters.

Dickerson ruled prior to the trial that the defense cannot present evidence which would suggest Arvizu had or claimed to have ties to the East Side Torrance street gang. East Side Torrance is a Hispanic gang that law enforcement officials confirm is present in Cochise County, particularly in the Douglas area.

The defense is also prohibited from eliciting testimony of specific acts of violence Arvizu allegedly committed but that Wilson was not aware of prior to the shooting. However, the judge is allowing testimony about Arvizu’s “reputation as to violence.”

Arvizu’s father testified that his son never messed around with firearms or weapons. However, another witness testified Arvizu had a machete several weeks before the shooting and he tried to sell to her.

The same machete was found in yard of the house Arvizu went to after being shot. As was a backpack, later determined to belong to Arvizu.

Another witness, Jose Luis Sanchez, testified the machete found at the house belonged to him not Arvizu. Detectives who looked at the weapon the morning of the shooting did not notice any blood on it, but they never tested it for fingerprints or DNA evidence.

Prior to trial, Wilson was held at the Pima County jail for nearly two years at the request of Cochise County officials. One of Wilson’s former cellmates at that jail was called to the stand last week by Zucco to testify that Wilson frequently talked about the shooting and appeared to show “no remorse.”

The witness admitted he was repaid for his jailhouse snitching through a sentencing consideration on charges out of Pima County.

Week 3 of the trial begins Sept. 29 with further defense testimony. Among the scheduled witnesses are a ballistic expert as well as a pharmacology expert expected to testify about the level of methamphetamine found in Arvizu’s system during autopsy.