Politics, Problems, and a Federal Turf War?

A pipeline to bring natural gas to Mexico has stirred up some controversy about its routing. The Arizona Daily Independent has printed three articles about some of the politics involved:

Grijalva uses national security concern to stop pipeline

The Pima County Kinder Morgan Shakedown

Sierrita Pipeline project: just the basics

The Altar Valley is desert grassland and home to several ranches, but the main problem is that it is also home to the Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge (BANWR) run by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (FWS).

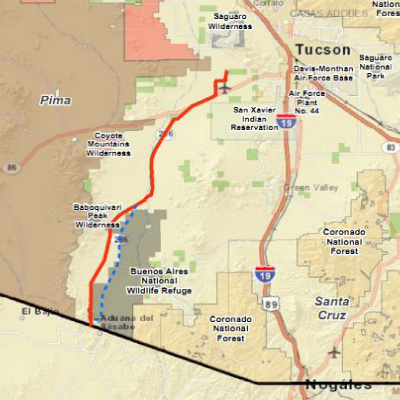

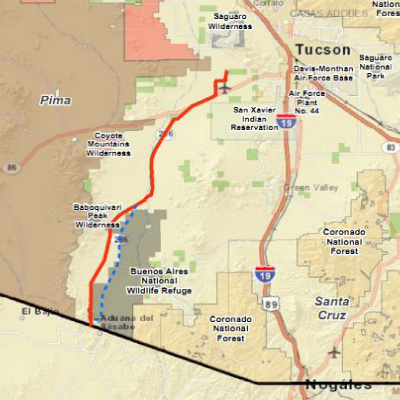

The map below shows the location. The red line shows the route preferred by FWS. The route follows Highway 286 and its right of way for an electrical line. However, the preferred route heads west into undisturbed land to avoid the Wildlife Refuge. The blue dashed line shows the continuation of Highway 286 through the refuge.

The logical route would be to continue the pipeline along the highway right of way, but FWS is fiercely protective of its Wildlife Refuge which is essentially a failed experiment to re-establish the Masked Bobwhite Quail in Arizona. More on that later.

The logical route would be to continue the pipeline along the highway right of way, but FWS is fiercely protective of its Wildlife Refuge which is essentially a failed experiment to re-establish the Masked Bobwhite Quail in Arizona. More on that later.

The Wildlife Refuge is a favored route for illegal entry and smuggling from Mexico. The FWS preferred route (red on the map) would establish yet another corridor for such illegal entry. According to one local rancher, that route would also require some condemnation of private land – eminent domain action to benefit a private company. The rancher asks, “if it is in the public interest enough for the Federal Government to allow a private company to condemn private land should that same Government not ante up its own land where appropriate?”

Another rancher points out that the favored route (red) will cross 206 ephemeral streams, which is expected to cause substantial erosion since the soils are highly erodible. If the pipeline were to follow the road through the Wildlife Refuge, it would cross 37 fewer intermittent and/or ephemeral washes than the chosen route. It would also cross through five fewer miles of existing designated “critical habitat” for the Mexican garter snake.

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) prepared an Environmental Impact Statement for the pipeline. They say essentially that FWS protests too much:

“We acknowledge that many of the impacts cited by the FWS could occur on the East Route

Alternative [following the road]. However, we believe that all of these impacts could be avoided, minimized, and mitigated through proper planning and Project execution. We do not concur with the FWS’ conclusions that these impacts necessarily would be unavoidable or significant because, regardless of the route chosen, Sierrita would be required to implement its mitigation plans… as well as our recommendations for reducing or eliminating environmental effects…

“Collocation of facilities is a generally accepted means to control the location of development and limit impacts on sensitive resources by keeping disturbance within established corridors. Installation of a new pipeline along an existing, cleared right-of-way…may be environmentally preferable to construction of a new right-of-way, and construction effects and cumulative impacts can normally be reduced by routing adjacent to a previously cleared corridor. While it does not overlap or abut existing rights-of-way for its entire length, the East Route Alternative is in an area that is already fragmented by linear facilities and is subject to ongoing disturbance from road and utility line operation and maintenance. By installing the pipeline adjacent to these existing features, the impacts cited by the FWS related to disturbance of wildlife, disruption of migration, degradation/fragmentation of habitat, wildlife-dependent recreation, and recreation would be substantially reduced or eliminated.”

To put things in perspective, below is a short history of Altar Valley and BANWR gleaned from FWS, local ranchers, and other sources.

The Altar Valley was first homesteaded by Pedro Aguirre, Jr. in 1864 as the “Buenos Ayres Ranch.” He had been running a stagecoach and freight line between Tucson and mines near Arivaca, Arizona and Altar, Sonora, Mexico. Aguirre drilled wells, built earthen dams, and created Aguirre Lake. This ensured a water supply for cattle in the Altar Valley.

As railroads opened new markets, cattle numbers in southeastern Arizona exploded. But an extreme drought from 1885-1892 killed at least 50% of each herd. The remaining cattle stripped the land bare. This occurred before establishment of modern ranching practice. When the rains returned, no grasses were left to absorb the water. The rain eroded the land, creating the washes and gullies we see today. The earthquake of 1887 may have contributed to the erosion by either raising the land or lowering the water table.

Between 1909 and 1985, Buenos Aires Ranch changed ownership several times. It became one of the most prominent and successful livestock operations in Arizona. From 1926 to 1959, the Gill family raised prize-winning racing quarter horses. During the 1970’s and 80’s, the Victorio Land and Cattle Company specialized in purebred Brangus cattle, which are well suited to hot, dry climates. The ranch sold bulls and bull semen nationally and internationally with some bulls selling in the hundreds of thousands of dollars.

In 1985, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service purchased the Buenos Aires Ranch, and it became a National Wildlife Refuge. FWS brought in pronghorn antelope and masked bobwhite quails (which promptly became food for coyotes and hawks). FWS abandoned wells and waterlines because they were “unnatural.” With the lack of water, much of the wildlife left. (More recently, FWS re-established some of the stock ponds.) The Altar Valley is the northern fringe of the bobwhite’s range. At the time of Refuge creation, a study of the bobwhite was going on at Las Delicias ranch. That study indicated that the bottom of the valley was too extreme for the quail.

A more detailed history is presented in the book Ranching, Endangered Species, and Urbanization in the Southwest, by Dr. Nathan Sayre (2002) University of Arizona Press.

Sayre recounts the history of cattle ranching in the Altar Valley by examining both the economics and ecology of ranching. The Altar Valley was a lush grassland, but one without perennial water sources. In a parallel story, Sayre examines the failed effort of the federal government to establish the Masked Bobwhite Quail in the region.

Sayre starts by exploring the history of the masked bobwhite quail, a subspecies of the northern bobwhite, from its discovery in 1880s, its disappearance around 1900, to its return to the Altar Valley in the 1970s. During this period, the masked bobwhite acquired great symbolic value among ornithologists and wildlife managers as a victim of cattle grazing. Sayre concluded that the effort to reestablish the bobwhite was doomed to failure because the Altar Valley is at the very northern extreme of the quail’s habitat. They die in freezing weather which occurs frequently in mid-winter on the Refuge.

Sayre notes that more than 25,000 captive-bred birds have been released on the Refuge at a cost of $68 million, but few if any survive. “Despite the removal of livestock, Refuge biologists have not succeeded in establishing a self-sustaining population of masked bobwhites.” “An ambitious program of prescribed burning, intended to simulate the natural fire regime of the desert grasslands, has not resulted in any change in the vegetation on the Buenos Aires.”

Even thought FWS has failed in its primary goal for the Refuge, it remains protective of its little kingdom to the detriment of the valley as a whole by requiring the pipeline to construct a new right of way through undisturbed grassland.