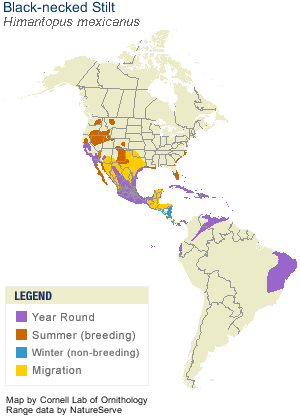

The Black-necked Stilt (Himantopus mexicanus) is a fun bird to watch as it noisily feeds along shorelines. (Listen to sounds). This Stilt occurs in the southern and western U.S. Its range includes the Great Basin, Sonoran and Chihuahuan deserts near bodies of water. The Sonoran Desert, south to the tip of Baja, California Mexico, is within its year-round range. You can see some at the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum where I took the photograph.

The Black-necked Stilt stands about 18 inches high and has a wingspan of 28 inches. It has a black head, neck and back over a white body. Its bill is long and black. One of its most striking features is its very long, red/orange legs. “ They have the second-longest legs in proportion to their bodies of any bird, exceeded only by flamingos.” “Five species of rather similar-looking stilts are recognized in the genus Himantopus.” (Source)

Stilts forage, often in groups, in shallow water or along shorelines for insects and other prey. Cornell Lab of Ornithology adds: “Black-necked Stilts wade in shallow waters to capture their meals of aquatic invertebrates and fish. They often consume such fare as crawfish, brine flies, brine shrimp, beetles, water boatmen, and tadpoles. They peck, snatch, and plunge their heads into the water in pursuit of their food, and will herd fish into shallow waters to trap them there.”

According to ASDM: “These are ground-nesting birds, whose eggs are well camouflaged and whose downy chicks can run about and find their own food shortly after hatching. Adults defend eggs or chicks with a repertoire of distraction displays. These birds are good runners and strong flyers.”

According to Cornell: “Male and female Black-necked Stilts trade off the job of constructing the nest. While one mate observes, the other scrapes into the dirt with breast and feet to form a depression about 2 inches deep. As they dig, they throw small bits of lining over their back into the nest. Most lining is added to the nest during incubation, and consists of whatever material is closest to the nest, including grasses, shells, mud chips, pebbles, and bones.” “ During breeding and during winter, they are strongly territorial birds, and are particularly aggressive to chicks that are not their own. When not breeding, Black-necked Stilts roost and forage in closely packed groups, often staying within a foot of each other. Black-necked Stilts are semicolonial when nesting, and they participate en masse in anti-predator displays. The displays include one in which nonincubating birds fly up to mob predators, and one in which all birds encircle a predator, hop up and down, and flap their wings.”

A more general note on shorebirds from ASDM:

Shorebirds in general do most of their foraging along the water’s edge, probing in soft mud or picking at the surface in search of tiny invertebrates. They belong to several related families. The largest shorebird group is the sandpiper family (Scolopacidae); nearly two dozen species of sandpipers migrate through the Sonoran Desert, but for the most part their presence with us is fleeting, a few days’ stopover as they travel between breeding grounds on Arctic tundra and wintering grounds on southern coasts. More relevant here are two long-legged waders and one plover that are with us for much of the year.

The avocets and stilts make up a small family, with only a few species worldwide. All are slim birds with long necks, thin bills, very long legs, and striking patterns. All forage in shallow water, feeding on small invertebrates. North America has one avocet and one stilt. Both have ranges which extend into the Sonoran Desert, where they seem to have benefited from human activity; most of their modern nesting sites are around the edges of artificial ponds.

Note to readers:

Index with links to all my ADI articles: http://wp.me/P3SUNp-1pi

My comprehensive 28-page essay on climate change: http://wp.me/P3SUNp-1bq