This article is re-posted from the Arizona Geological Survey e-magazine. Article by Michael Conway.

See original: http://blog.azgs.arizona.edu/magazine/2017-11/arizonas-monsoon-season-drives-earth-fissure-activity

Geoscientists agree, there is no such thing as an earthquake season. The tectonic forces producing earthquakes are inured from changes in meteorological or astronomical conditions; the latter involves fluctuation in gravitational forces due to the position of Earth’s Moon.

Arizona does, however, have an earth fissure season. A season when earth fissures are more likely to first appear or undergo renewed activity. Central and southeastern Arizona’s earth fissure season accompanies the onset of torrential rainfall of the summer monsoon, from mid-June to late September, with most precipitation occurring from mid-July to mid-August.

In southern and western Arizona, Cochise, La Paz, Maricopa, Pima and Pinal Counties all host earth fissures. In these five counties, we‘ve identified nearly 30 discrete earth fissure study areas, each with its own history, and comprising a collective 170 miles of mapped fissures and an additional 180 miles of reported but unconfirmed fissures. (Why unconfirmed? Three principal reasons: 1) ground disturbance has effectively masked the fissure; 2) built infrastructure now covers the fissure; 3) the feature was incorrectly identified as a fissure initially.)

Release of 4 revised earth fissure maps

Each monsoon season finds the AZGS’ mapping team in the field addressing new leads and revisiting fissures with a history of activity. Mapping results are compiled on existing earth fissure study area maps, which are then revised, re-versioned, and released online at the interactive Natural Hazards in Arizona site. At the same time, we release an updated ESRI spatial data file (.shp) and Google Earth KMZ file, ‘Locations of Mapped Earth Fissure Traces in Arizona’, versioned to the date of release, in this case 06 Nov. 2017.

This year we are releasing revised maps for four earth fissure study areas (Figure 1):

- Apache Junction, Maricopa – Pinal Counties

- Chandler Heights, Maricopa County

- Tator Hills, Pinal County

- Three Sisters Buttes, Cochise County.

Two of these, Apache Junction and Chandler Heights, have largely shifted from agricultural lands to residential or industrial use lands, markedly increasing the hazard and risk that accompanies fissuring.

Fissure activity ranges widely within and between study areas. Not all fissures are created equal; and not all fissures display activity each monsoon season. Most study areas retain some active fissures that either display slow incremental expansion, or dramatic episodic growth powered by eroding sheet flow accompanying torrential rains; sheet flow fans across the valley surface as a thin sheet of water spilling into open fissures eroding sidewalls and causing gullying.

Existing fissures frequently capture numerous drainages leading to incision (headcutting) on the up-channel side. Fissures often form orthogonal to the natural drainage direction, so channels and washes intersected by the fissure deliver water during and after rains.

With reduced groundwater harvesting and waning subsidence, fissures may transition from active to inactive status. When this occurs, they become sediment traps for wind- and water-borne sediments – clays, silts and sands – that subsume the fissure, masking its diagnostic morphology – a wide open throat, steep to inclined sidewalls and a hummocky, irregular base. Reactivation of dormant, partially filled earth fissures, may occur if heavy runoff, coupled with even modest land subsidence that produces tensional forces sufficient to reopen the fissure, counters the ‘healing’ process, leading to a wider and more deeply incised fissure.

Apache Junction: Case Study of a Reactivated Fissure

The Apache Junction earth fissure study area map was first released in April 2008. Over the past several years AZGS Earth Fissure manager Joe Cook has revisited the Apache Junction virtually, via Google Earth, and physically to examine new or reactivated earth fissures. According to Cook, ‘there’s about 0.8 miles of new fissures in Apache Junction since April 2008. Many of the new fissures formed parallel to existing fissures or connected gaps in formerly discontinuous fissures.’

On the morning of July 24, 2017, following heavy rains on the late evening and early morning hours of 23-24 July, nearly 320 feet of fresh fissure opened near West Houston Ave., Apache Junction (Figure 2). This new feature is part of a larger fissure zone that stretches for more than 2 miles from near the junction of Baseline and Meridian Roads to south of West Guadalupe Road (Figure 2a). The fissure complex tunnels below streets, state trust land, private property, and large power lines.

According to Joe Cook’s report; ‘The fissure cracked West Houston Ave and an open void was visible beneath the road through a collapsed pothole. The road was closed to vehicle traffic immediately, but additional road collapse occurred over the days and weeks that followed. Large open depressions approximately 5-15 feet across and up to 8 feet deep, partially filled with collapsed material, were visible on private property to the south of Houston Ave. These open depressions were connected by parallel cracks beginning at Houston Ave to the north. Hairline cracks continued south of the southern-most depression for approximately 80 feet. Locally, a void space was visible below the hairline cracks indicating a strong potential for additional collapse.’

‘North of Houston Ave, the new fissure paralleled numerous, active and inactive, older fissures across the undeveloped desert floor. Additional reactivation and collapse along previously mapped fissures was observed beneath the powerlines in the southern part of the Apache Junction Study area.’

‘The cause for collapse of the fissure beneath Houston Ave is probably related to years of subsurface erosion along a buried earth fissure trace which intercepts rainwater from numerous drainages captured by the open portion of the fissure north of Houston Ave. During heavy rain events a substantial volume of floodwater is delivered to the fissure in a drainage ditch adjacent to the north side of W Houston Ave. Waning flow in this drainage ditch was observed to be pouring into the open fissure on the morning of July 25, 2017. No flow in the drainage ditch was observed downstream of the intersection with the earth fissure. The water draining into the fissure was not visible along the fissure anywhere else; water poured into the fissure in a free fall of about 8 feet before disappearing to unknown depths. Void space for further collapse must be substantial, which suggests that continued collapse following heavy rains is possible.’

By August 15, 2017 the collapsed portion of the fissure within the private property south of Houston Ave had been filled, presumably by the owner. But additional damage was evident, and the collapsed section of Houston Ave. remained closed.

Tator Hills: Case Study of a Fresh Fissure

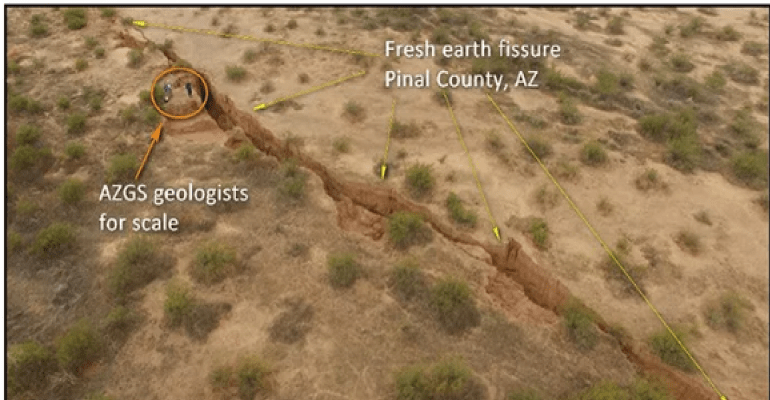

Over the past several years, Tator Hills in southern Pinal County displayed the greatest fresh fissure activity of the four study areas (Figure 3). Imagery served by Google Earth shows that between Mar. 2014 and Dec. 2014, a mile-long, north-south trending earth fissure unzipped about 13 miles south of Arizona City. Sometime after March 2016, the fissure extended an additional ¾ mile to the south. The appearance of this fresh, 2-mile long fissure in an area of modest land subsidence ~ 1 inch (3 cm) annually over the past decade, and otherwise lacking active fissure formation since the early 1990s, was surprising (Cook, 2017).

Applying drone technology to fissures. In Jan. 2017, AZGS geoscientists captured a real-time synoptic view of the newest Tator Hills fissure using a DJI-PhantomTM Drone. AZGS research scientist Brian Gootee piloted the drone and captured videos at 2.7K horizontal resolution, as well as 100s of high resolution, 12 Mb static JPEG images. The latter were stitched together using AgiSoft PhotoScanTM software and analyzed using both AgiSoft PhotoScanTM and ESRI’s ArcGISTM.

At our AZGS Youtube channel, the Tator Hills fissure videos have been viewed an astounding 780,000 times! See Drone technology examining an earth fissure or Drone video of a fresh earth fissure, Tator Hills, Arizona.

The drone’s bird’s-eye view yielded a suite of derivative products – oblique orthoimagery, relief/slope map, digital elevation model (DEM), and topographic maps with contour interval of 1- to 2-feet (Figure 4) – that afford a fresh view of fissure geometry, structure, and topography that may yield new insights into the formative and evolutionary processes of fissures.

Chandler Heights and Three Sisters Buttes. Since release of earlier mapping, we documented subtle changes in some fissures at Chandler Heights (2016), Maricopa County, and Three Sisters Buttes (2012), Cochise County. Chandler Heights infamous ‘Y-Fissure’, so called because of its Y-shaped geometry, remains active but the dramatic reopening and lateral extension observed in previous years has not recurred over the past several years. Nonetheless, the ‘Y-Fissure’ remains of great interest, in part because it winds through neighborhoods in east Queen Creek.

Agriculture is the economic engine that drives Cochise County. The Three Sisters Buttes study area lies several miles southeast of Willcox Playa. Groundwater withdrawal and concurrent basin subsidence continues there unabated and from May 2010 to April 2017, maximum subsidence in the basin reached 9.8 – 15.7 in; 5 to 15 times greater than subsidence observed in the Tator Hills. In rural Cochise County, fissures chiefly threaten roads and pipelines and road signs warning of fissures is a common sight (Figure 5).

Some Observations & Final Thoughts

For the foreseeable future, earth fissures remain a geologic hazard in central and southeastern Arizona. With urban and suburban areas aggressively expanding into former agricultural areas, county and municipal planners may anticipate new and renewed incidents of costly and potentially hazardous impacts, as evinced by the recent damage to the W. Houston Rd. and nearby industrial plant in Apache Junction.

The state of earth fissures in Arizona. Nonetheless, there is hope on the horizon for a diminished threat from earth fissures. According to a recent blog post by hydrologist Brian Conway (Arizona Dept. of Water Resources), ‘Land subsidence rates within the Phoenix and Tucson Active Management Areas (AMAs) have decreased between 25% and 90% compared to the 1990s. This is a result of decreased groundwater pumping, increased groundwater recharge, and recovering groundwater levels in the two AMAs.’

Controlling groundwater pumping reduces basin subsidence, which should in turn re-establish hydrostatic equilibrium across impacted basins, thereby reducing the extensional stresses that lead to fissure formation.

Since 2007, systematic mapping of fissure study areas in Maricopa, Pima and Pinal Counties has uncovered few new earth fissures. Moreover, many fissures mapped between 2007 and 2009 showed physical evidence of having formed years or decades before. It could well be that the rate of earth fissure formation in most study areas reached its apex in the latter quarter of the 20th century. If so, land managers in these impacted areas should anticipate seeing fewer new fissures forming and, perhaps, waning reactivation of existing fissures.

In Cochise County, where groundwater pumping and basin subsidence continues unabated, we anticipate new fissures forming annually and existing fissures reopening.

Note of caution. There could be a substantial time-lag between reduced pumping, waning subsidence rates, and the end of new or renewed fissuring. By way of example, subsidence in the Tator Hills area has slowed substantially since the latter quarter of the 20th century. From 2004 to 2017, total subsidence proximal to the 2-mile long fissure was between 1.6 to 3.2 inches; a magnitude of subsidence that seems inconsistent with the formation of a 2-mile long fissure. This fissure may have formed years before, only to break the ground surface in 2014. This could be true of concealed fissures in other study areas, too. We strongly recommend that civil authorities, farmers, contractors, and the public remain on the alert for the sudden emergence of rogue, outlier fissures.

Final Thoughts. The AZGS fissure mapping team continues to monitor earth fissure study areas, both virtually, via Google Earth and fresh National Agriculture Imagery Program (NAIP) imagery, and physically by returning to study areas. We confer regularly with county and municipal authorities regarding reports of reactivated or new fissures. Last, we remain aware of the potential of fissures forming in areas where the imbalance between groundwater harvesting and recharge leads to measurable basin subsidence, such as in agricultural lands of Cochise County and the McMullen Valley of Maricopa and La Paz Counties.

Related Articles:

References

Arizona Land Subsidence Group, 2007, Land Subsidence and Earth Fissures in Arizona: Research and Informational Needs for Effective Management: Arizona Geological Survey Contributed Report CR-07-C, 29 p.

Conway, B., 2017, That sinking feeling: state-of-art technology at work on Arizona subsidence finds that you’re not imaging it. Arizona Geology Blog, 27 July 2017.

Cook, J.P., 2017, Discovery of a large earth fissure in the Southern Picacho Basin, Pinal County, Arizona. Arizona Geological Survey Open-File Report, OFR-17-01, 7 p., 1 appendix.

Cook, J.P. 2017, Internal report on fissuring in the vicinity of W. Houston St., Apache Junction, Pinal County.

Harris, R.C., 1999, Field Guide to Earth Fissures and other Land Subsidence Features in Picacho Basin. Arizona Geological Survey Open File Report, OFR-99-26, 55 p.

Schumann, H.H., and Cripe, L.S. (1986). Land subsidence and earth fissures caused by groundwater depletion in Southern Arizona, U.S.A. In A.I. Johnson, L. Carbognin & L. Ubertini (Eds.], Proceedings of the 3rd International Symposium on Land Subsidence, Venice, Italy, 19-25 March 1984 (pp. 841-851). International Association of Hydrological Sciences, Publication 151.

Slaff, S. (1993). Land Subsidence and Earth Fissures in Arizona. Arizona Geological Survey Down-to-Earth Series #3, 30 p.