LOS ANGELES – Can’t leave the house without getting bitten? Legs swollen from scratching? Welcome to the crowd. Because yes, the mosquitoes are worse this year.

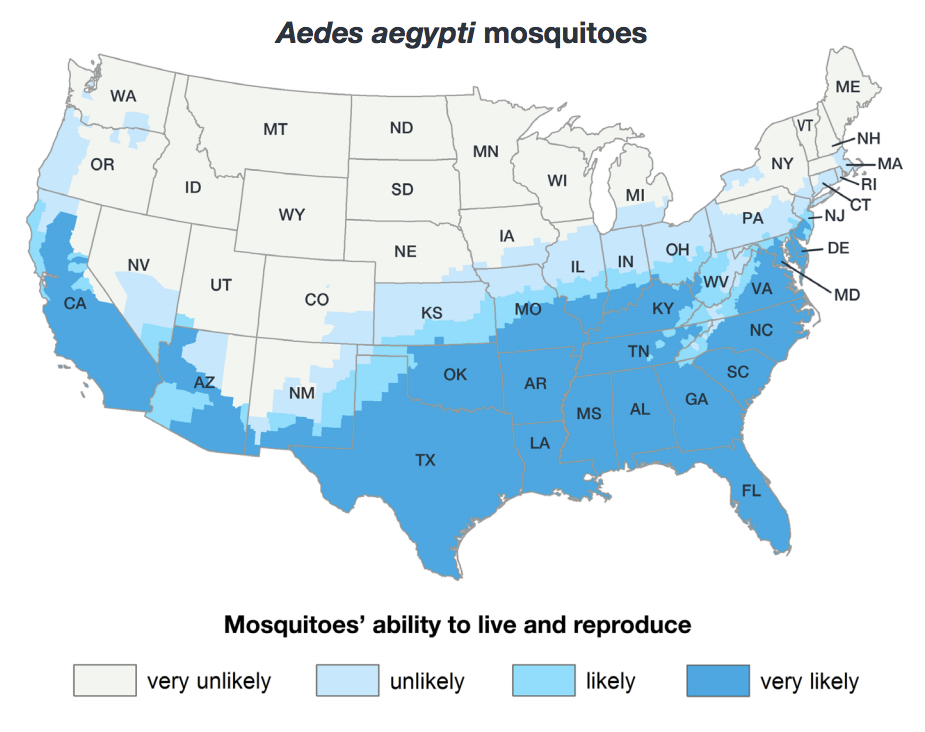

Why? There’s a new type of mosquito hunting across the southern United States. You might have heard of it – the Aedes mosquito – which first showed up in 2010.

It’s even present in areas experiencing drought, such as the Southwest. It’s way more vicious than the most common mosquito, known as the house mosquito, or the Culex.

Unlike the Culex, Aedes mosquitoes bite during the day. And they go for the legs and ankles, instead of buzzing around your ears, so you can’t hear them coming.

“They’re sneaky biters,” said Yessenia Avilez, an inspector for the Greater Los Angeles County Vector Control District.

It’s Avilez’s job to find and destroy the Aedes mosquito. And on a hot day in August, KPCC reporter Emily Guerin went along for the kill.

The bug hunt begins

It’s 8 a.m., and Avilez and her mosquito-killing partner, Faiza Haider, park their big white truck on a steep street in the Echo Park neighborhood of Los Angeles.

It’s their second appointment of the day, and they have at least six more to go. Inspectors are busiest in the summer, when the heat speeds up the Aedes’ reproductive cycle. That means the invasive mosquito infestation could get worse in the future, as temperatures continue to rise.

Avilez and Haider wear visors with an embroidered mosquito on the front and shiny Vector Control badges.

They bring a few things to every appointment: a big black tool box – they call it “Fat Max” – that includes containers to bring mosquitoes and larvae back to the lab, their flashlights, pamphlets to give to residents and their mosquito-catching vacuum.

They call it the “aspirator,” but it’s really just a leaf blower with the motor reversed, so it sucks air (and bugs) in instead of blowing out.

Once they get into the backyard, Haider and Avilez fan out.

“We’re looking for standing water,” Haider said. “Something as small as a bottle cap can breed mosquitoes.”

That’s one key difference between the invasive Aedes and native Culex mosquitoes. Culex prefer to lay their eggs in big sources of water, such as swimming pools, but the Aedes mosquitoes hardly need any water at all.

Both mosquitoes, however, can carry diseases: Culex has successfully transmitted West Nile to six people in LA County already this year, while Aedes can transmit Zika virus and dengue fever – although that hasn’t happened yet. Arizona officials also report six confirmed or probably cases of West Nile in 2018.

The women pick up potted plants, checking to see if the trays underneath hold stagnant water. They peer into bamboo thickets, looking for places where water collects. They inspect doggy dishes, looking for larvae. And they take out their flashlights to check out empty buckets and pots, looking for the thin white calcium line where water used to be.

“The invasive mosquitoes likes to deposit its eggs right above the water mark,” Haider said. And the eggs can lie dormant for years, just waiting for the pot or bucket to be refilled again.

That’s why when she and Avilez find a line of eggs in a dry pot, they’ll take it back to their lab and destroy it, or have the resident give it a good scrub with soap or bleach.

Jane Stephens Rosenthal is scratching her arms while she watches. She’s lived here for five years and called Vector Control because the mosquitoes have never been this bad.

“I was out here on a call at 9:30 a.m. for half an hour, and my legs were totally bitten,” she said. “They’re just nasty.”

After hunting around for 15 minutes, the women don’t find any standing water, or dried eggs. So they decide to try to catch a mosquito, to make sure it is, in fact, the invasive Aedes that’s been bothering Stephens Rosenthal.

Haider takes out the aspirator and holds it up like a squirt gun, jabbing it towards a mosquito buzzing near the back of the yard. She looks like a Ghostbuster.

If she catches one, she’ll slam the lid on the tube of the leaf blower and check to see what kind of mosquito it is. But this time, the little bugger got away.

As the women turn to leave, Stephens Rosenthal offers a tip: There could be an uncovered rain barrel at the neighbor’s house.

The menace next door

It’s not uncommon for mosquitoes to breed at one house and fly over the fence to bite the people next door.

“This mosquito doesn’t travel very far,” Avilez said. “It stays very close by to where it just hatched.”

So the women head one house down and ring the doorbell. No answer. But through the fence they can see, beneath the deck, a giant, uncovered rain barrel. They poke their flashlights through the fence, shining it at the hole.

“That’s a point of entry,” Avilez said, “so mosquitoes can just fly in, deposit their eggs and fly out. It’s a perfect environment. It’s shaded. There’s people. There’s food.”

Ideally, they would treat the rain barrel with larvicide right away.

But instead, they tape a note on the door, and they’ll come back in three days if the homeowner doesn’t call.

It’s illegal, at least in California, to ignore a source of mosquitoes on your property, and you can be fined up to $1,000 a day for refusing to fix the problem.

This story is part of Elemental: Covering Sustainability, a new multimedia collaboration between Cronkite News, Arizona PBS, KJZZ, KPCC, Rocky Mountain PBS and PBS SoCal.