Destination Bay Area:

Do you balk at the puerile pap of the propertied press? Join us in a tub of Insurgent! Let it wash over you…” ~ David Castro

Following unprovoked police attacks on student demonstrators against the House Committee on Un-American Activities in May 1960, the San Francisco Bay Area – especially Berkeley – became a magnet for young people fed up with Cold War fear and political intimidation.

The Silent Generation and the Beat Generation were giving way to a new generation no longer willing to quietly accept a status quo that included political repression, racial segregation and the unrestrained use of military power both covert and overt.

Indeed, veterans of Black Friday the 13th who were knocked down the marble stairs of San Francisco’s City Hall by police with clubs and high-pressure fire hoses claim, with pride, that “We started the Sixties!”

A not-so-young man attracted to the new and hopeful swirl of activity was a San Quentin inmate who had been a heroin addict, thief, and convicted criminal. His name was Dave Castro, and he was my friend.

While Students for a Democratic Society had been founded in 1960, it was several more years until the release of the Port Huron Statement and visibility for the emerging student movement. The anti-HUAC demonstrations, the arrests, and the establishment of ongoing organizations like BASCAHUAC (Bay Area Student Committee for Abolition of the House Un-American Activities Committee) – were sparks to movements that erupted a few years later. I was a high school dropout, a blue collar worker who was elected vice-president to that group.

Later milestones of this leftist movement were the Sheraton-Palace Hotel and Auto Row sit-ins for hiring integration; the contingents of Freedom Riders going south for integration, Freedom Summer registering voters in the deep south; the Free Speech Movement at Berkeley’s University of California and massive peace marches against the growing war in Vietnam. There was also support for farm worker union organizing.

This was the era of the rise of a New Left; and the breathing of life into a moribund Old Left – decimated after 1956 by U.S. Government imprisonment of its leaders, the Stalin revelations and the Red Army’s smashing of the Hungarian workers’ reveal. The Communist Party founded the W.E.B. DuBois Clubs as an attempt at a broad new youth arm.

Addict, Thief, Ex-Con, Poet, Lover

We, as artists responsible to the future as well as the past, wish to exercise our art freely, to document the profound social changes that form the very fabric of modern life, without sacrificing art and honesty to the demands of the quick sale and volume turnover. — David Castro

I first met Dave Castro around the DuBois Club’s magazine, Insurgent, in 1966 after he was released from San Quentin – not for the first time. He had been in “Q” and wrote to the DuBois Club that he was up for probation and needed to be “gainfully employed.” Insurgent named him Editorial Assistant, at a $10 per week salary, but there were rarely any funds available.

The late Carl Bloice was the Editor and Celia Rosebury was the Managing Editor when the magazine’s first issue appeared in March, 1965, selling for a quarter. With stories about the Beatles, the Free Speech Movement, African American legislators in Mississippi during Reconstruction, job discrimination in the Bay Area, plus poetry and song, Insurgent mixed left-wing politics with popular culture, hoping to reach a wide audience. Dave had two poems, a letter, and a book review in that issue, along with ghost-written text for a photo essay.

He was arrested again later in 1965 and sent back to prison, writing to Celia and her new husband, cinematographer Stephen Lighthill, that he wished he could have put a lampshade on his head and danced at their wedding. He returned to the Insurgent milieu when he was released, sometimes using a credit card to jimmy the lock on the Lighthill’s apartment and be a surprise visitor when they returned home.

For a 32-year old former heroin addict and convicted burglar and car thief – he described himself as a “professional dirty guy” — it was a new and exciting world. He had talents that were welcomed by some of the young leftists he hung out with, skills that brought him the attention and respect he craved.

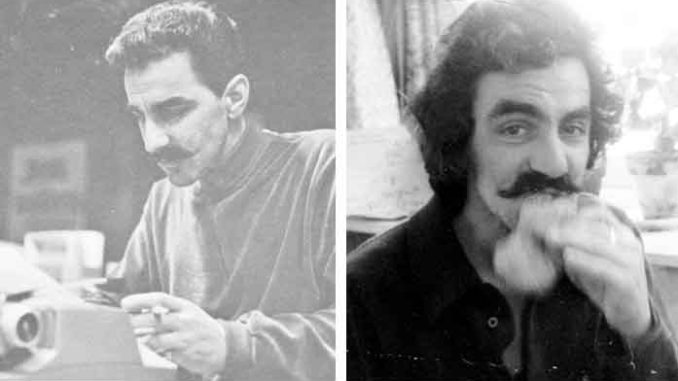

Dave was intelligent and attractive, with bushy black hair and a big mustache, he talked softly, and he was a writer and poet. Always gentle with people, Dave had no problem attracting girlfriends. While he stayed off heroin at times, he ignored DuBois Club/CP strictures against all drugs – made you vulnerable to the law and therefore potentially a stoolpigeon — and smoked his share of marijuana, and drank red wine in copious quantities with me. I recall that we got high together one evening and I received an urgent call that meant I had to go somewhere; Dave taught me how to drive while stoned, how to judge distances.

He never talked to me about his youth, his family, his upbringing, usually changing the subject by saying his family derived from Spanish land grantees in the 1800s from the Monterey-Santa Cruz area. Whether this was truth or fantasy I never knew, but he had clearly done his homework. Dave grew up in San Francisco with his parents and sister, near the Glen Park neighborhood’s Goat Hill. He retained close ties to his neighborhood and friends over the years.

What seems to be the case, although not completely verified, is that his father was Raymond Henry Castro, of Spanish descent, who was an infantry lieutenant in World War I. Raymond may have incurred injuries there which left him blind. He found work with other sight-impaired people at a nearby broom factory run by Lighthouse, making corn brooms from straw. Gil Johnson, who supervised the workshop’s activities, recalls that that despite spinning machinery and stitching, there were no serious injuries and while safety inspectors were concerned about blind people around moving machinery, no action was ever taken by them. The broom workshop, begun in the early 1920s, closed in 1981.

Raymond Castro died in 1970 at age 75 and was interred at Golden Gate National Cemetery in San Bruno. Dave’s Irish mother, Mary Alice Cronin Castro, was unable to prevent her son’s beatings by his father. Why Dave did not simply run away from his sightless tormentor remains a mystery. I don’t know when his addiction came, but I know that before I discovered alcohol I found that if I could not win positive attention and approval from my parents there were many ways to attract negative attention, and to show them how tough I was. Mary Alice passed away in 1959 at the age of 65. She is interred next to her husband.

Dave freely acknowledged that he had been a heroin addict, and that he stole to get the money to feed his addiction. His new addiction, he said, was to The Revolution. His writing, he hoped, would further that cause. He had, he said, an idea for a novel that would hasten it. To my knowledge, he never wrote it, although he reportedly later wrote a film script that was meant to accomplish the same revolutionary result.

Dave was a free spirit unable and unwilling to kowtow to the Party Line of the day, to bureaucratic decision-making that excluded those being decided for – he had enough of that in prison. He also continued using his drug of choice, heroin, and he knew that would never sit well with the apparatchiks. Dave had an extraordinary ability to compartmentalize the many facets of his life.

On March 6, 1966, at 2:45 a.m, the DuBois Club national headquarters on McAllister Street in San Francisco was dynamited and destroyed. The CP’s youth arm had gotten some publicity for refusing to register as a “communist-front” organization, and “ultra-rightists” and “racists” were immediately blamed. The 1966 May-June issue of Insurgent announced that the magazine was moving to Chicago along with the national office of the DuBois Club. The organization dissolved in 1970 as the parent CP imploded once again following Soviet tanks rolling into Prague to suppress Czech efforts to create “socialism with a human face.

Sons and Daughters

(This contemporary historical drama is) frankly partisan, full of their laughter and music, their noisy humanity, their deep concern, it is the story of people, mostly young people, struggling to breathe life into the ideals of democracy and justice they have been taught as Americans. They see these ideas suffocating in the atmosphere of hypocrisy and conformity generated by the impact of the war machine upon all our social institutions…it reflects their efforts to rescue democracy and justice…. ~ David Castro

In October, 1965, a two-dozen-city coordinated protest against the Vietnam War was organized at the University of California in Berkeley by a new Vietnam Day Committee (VDC) coalition whose leadership included Jerry Rubin and Abby Hoffman.

Well-known Bay Area photographer Jerry Stoll, with cameraman Stephen Lighthill – soon to marry Celia Rosebury — worked with the VDC to cover the events on film. Stoll set up American Documentary Films (ADF), enlisting Dave Castro and others to assist. Jerry had the ability to attract talent willing to work for virtually nothing, or for free. Although the VDC had commissioned him to make a short film for use in organizing, Stoll set out to make a full-length movie about the Bay Area demonstrations and the war.

After an all-day teach-in at UC-Berkeley on October 15, over 15,000 people marched peacefully against the war. Their destination was the Oakland Army Terminal, but they were met at the Berkeley-Oakland border by hundreds of police in riot gear, creating a solid wall to stop them. They marched back to Berkeley Civic Center Park, where the teach-in continued, along with music from Country Joe and the Fish and other local musicians. The marchers pledged to return the next day.

Some 5,000 showed up, and at the border the police asked them to sit down to avoid any violent confrontations. A small group of Hell’s Angels motorcyclists were also at the border and attacked demonstrators while poet Allen Ginsburg led a chanting of “Hare Krishna.” The police stopped the gang, and Ginsberg, along with Merry Prankster Ken Kesey, arranged to meet with the motorcycle gang’s head, Sonny Barger. They reportedly met that night, dropped acid together, and defused threatened attacks on future marches.

Jerry Stoll, who died in 2004, gathered an impressive group of supporters to make the film, including local jazz icon Virgil Gonsalves to write and perform original music, and jazz singer/songwriter Jon Hendricks to do a pair of songs for the film, with the Grateful Dead backing him. A 45 rpm record, with Sons and Daughters on one side and Fire in the City, a song written by Peter Krug about urban black uprisings, on the other, was produced. Grateful Dead management soon sought to have the band’s name removed because it was “too political.” Dave Castro, brought into ADF by Stephen Lighthill, wrote much of the film’s narration and text for the publicity brochure, and sometimes slept at the ADF office when no one else would take him in.

Sally Pugh, associate editor and music editor for the film, remembers that Dave wrote draft after draft of the film’s narration, only to have it rejected by Jerry Stoll. Writing a film was much different than writing a story or poem, and Stoll had his own vision. One day Dave came in with a big smile and said, “Okay, Stoll, I’ve been up all night working on this; I finally got it!” They ran the film-in-progress without sound while Dave read his narration aloud.

Before the film had finished Jerry Stoll turned off the projector and said, “No, you didn’t get it!” Dave took each sheet of paper, crumpled them into balls and threw them away. If he was angry, he didn’t let it show, and laughed at himself. It took awhile longer, but he did finally “get it,” even if Stephen Lighthill thought the final result, fitting Stoll’s “grandiose vision” and read in the film by Sally Pugh’s sister Janet, was “overwrought, simplistic and written for the already-committed.”

Nelson Stoll – working as sound recordist/editor for his father at ADF — remembers that Dave often hung out with a fellow inmate from San Quentin, Al Perez, who partnered with Jerry Stoll’s daughter for awhile, and there were rumors of the two of them participating in less-than-legal activities, including burglarizing Stoll’s apartment for a single item of interest.

Perez had earlier demonstrated his lock-picking abilities to Stoll, and knew that he had obtained a gun for home protection in the increasingly violent Haight-Ashbury District. Stoll recalls: “Both Dave and Al were the friendly, straight-faced surprised cons when I relayed the event to them. They told me it’s best to not have a gun and suggested I not get another.” Dave Castro was really good at keeping the personal, political and criminal aspects of his complicated life from mixing – except when he chose otherwise.

The movie was called Sons and Daughters, and was released in 1967, winning an international film festival prize. While working on the film, Dave and his ADF allies developed a Mobile Street Cinema, learned from Cuba, to show film on the side of a truck, projecting from the inside. Clips of the war, and of demonstrations opposing the war, were shown wherever an audience could be found. Dave and the truck would drive up to a crowd, such as the early morning longshore pay line on San Francisco’s Embarcadero, and start the films. The sounds of gunfire and explosions from the war grabbed instant attention.

ADF opened an office in New York City, and was always on the verge of running out of money. Cameraman Stephen Lighthill doubled as bookkeeper/accountant/clockwatcher and knew that the film was “deficit financed” and couldn’t pay its bills. At one point Dave Castro and Jerry Stoll invented “revolutionary currency,” fake money with cartoon characters on the bills instead of dead presidents. When funds were short staff was paid with the fake currency and told it could be redeemed “after The Revolution.”

Nelson Stoll left ADF to pursue his own career, later winning an Emmy award and two Academy Award nominations for sound recording. Sons and Daughters was a good learning experience for Stephen Lighthill’s early film-making career, but — no longer willing to bear the pressure of “deficit financing”– he left ADF in late 1966 to free-lance as a cameraperson for CBS News. He was honored in 2018 with the American Society of Cinematographers’ President’s Award.

Dave Castro got married in 1967. Susan was a “red diaper baby” born into the Old Left. Dave was thrilled to be the object of this feisty young woman’s attention, and they were married in Celia and Stephen Lighthill’s living room by radio announcer Scott Beach. This kind of relationship was brand new to Dave and he was the first to admit that he was a neophyte at real romance. He was not very good at it and the relationship soon ran into problems.

According to several women who partnered with him, Dave’s relationships showed no meanness towards women, never trying to degrade them. Unlike many men of the New and Old Left who could not practice what they preached about gender equality, Dave Castro preferred the company and intellect of women over men, and was always complimentary to them.

Women liked his flowery speech and ability to talk intelligently about almost anything, to have real conversations without traditional gender roles getting in the way. Dave’s continuing heroin use and other less-than-legal activities were the issues that generally hastened their end. He was, as one ex-lover said, “unable to be a partner.” Yet he rarely lacked female companionship.

Dave also respected and could be friends with women who rejected his advances. While Sally Pugh made it clear she was not interested in a sexual relationship, they became close friends during the ADF days. Dave talked to her about his love of heroin, but it was “pretty sad and sobering” when she walked in one day to find him and his pal Al Perez passed out with hypodermic needles sticking out of their arms. Sally’s focus shifted away from ADF in 1972 with the birth of her first son and she gradually lost touch with Dave.

I worked as a warehouseman and was an active shop steward in Local 6 of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU). Somewhere along the way, probably in 1966 after he was released from prison, Dave told me he needed a job. While most of the warehouse jobs came through the union hiring hall, there were a few places where the union only had the “right to refer” applicants. I made inquiries of the Local 6 officials, and Dave was referred to a small sundries warehouse in Brisbane, and he got the job.

Since I worked at a distribution center a few miles further south, I drove him to work, and sometimes Dave would chuckle, pointing to a building we were passing. “I went in through the skylight on the roof there,” he said, referring to his burglar days. Dave “liberated” a silver-filigreed ebony pipe to give to me. I accepted it with gratitude. And told him to be careful

Kicking Back in Santa Cruz

Democracy is the triumph of the idea that each individual has the right to participate in the decisions that affect his life. To do this he must have access to information and open dialogue; he must have the right to dissent. We are determined to fight for these rights, to preserve this triumph. ~ David Castro

In early 1968, after a brief stint as a Bay Area organizer, the ILWU asked me to be their one-person Washington, D.C., office. With my first wife, Elaine Millán, and our two young children we moved cross-country, leaving the Bay Area and Dave Castro behind. It soon became clear to me that in the nation’s capitol, one either became like everyone else working The Hill, or got out. After three and a-half years I chose to get out, and took advantage of an opportunity to work for Local 6 that would have me based in Salinas. We bought a ramshackle house in Prunedale in the hills north of town and I went to work negotiating, grievance handling and organizing.

Dave Castro was already in Canada, hiding out, when the Montreal Western Hemisphere Anti-War Conference took place in November, 1968. More than 1,000 people showed up, with not-yet-president of Chile Salvador Allende as keynote speaker. Dave had hooked up with a local journalist, living with him for awhile and sharing drugs, and conference delegates close to them whispered of the two of them being involved in mysterious and “nefarious”activities.

Speculation about Castro included running guns to the Black Panthers, because Dave was friendly with fellow prison veteran and Panther leader Eldridge Cleaver, who was among the conference speakers. Ot perhaps he was helping the Quebec Liberation Front, whose tactics included murders, kidnappings and bombings – “propaganda of the deed”— or just assisting American draft resisters. Cleaver, who had visited with Dave in San Francisco, jumped bail after leading an armed Black Panther attack on Oakland police in retaliation for the murder of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and took refuge in Cuba.

A lover from California, who thought she had a nearly year-long exclusive relationship with Dave, visited him in Canada. He had dyed his thick black hair, part of a disguise to avoid arrest for those rumored “nefarious activities.” He also had another girlfriend, and the California relationship bit the dust. Dave’s skill at compartmentalizing the different parts of his life failed him this time.

I don’t remember corresponding with Dave during the D.C. time, but I must have, since when I returned to California in autumn of 1971 I knew that he was living in Santa Cruz. My organizing tasks included trying to bring the Lipton Tea factory back into the union. Lipton had closed down in San Francisco years before, terminating hundreds of union members, and then opened a full-blown non-union facility in Santa Cruz. I had the name of one union-friendly contact, and from her developed a list of workers to visit when they were off work. I spent several days a week in Santa Cruz, and frequently visited Dave and his partner, Sara.

Sara was working in American Documentary Films’ New York office when she met and fell in love with the charming poet. Dave was “crazy about Sara.” The marriage with Susan had ended. Dave and Sara settled in Santa Cruz, where I found him calm and enjoying each day with his new love. Sara was smart and robust, coming from a Midwestern farm before becoming a political activist and finding a home with ADF. In Santa Cruz they used FCC rules for community TV access to produce a radical news show on local cable television.

One day Dave told me that the TV studio had been raided by right-wingers who ripped off $20,000 in equipment and spray painted anti-communist slogans on the walls. I blinked, and asked Dave how much he would get back from the insurance and if there was any chance they could trace it back to him. He blinked, and said that I was the only person who could have asked him that.

He asked me please not to mention it to Sara; she believed his vigilantes story. Later he told me that some of the money went for guns for the Black Panthers, and that he had been caught with a trunk full of weapons – so the Canadian rumors had a basis in fact. He got off on a technicality, he claimed, and split to Canada for awhile. He didn’t mention that he went in disguise and with an assumed name.

With the benefit of hindsight, I should have taken a step back, but I didn’t. I never believed, now or then, that it was all right to get somebody else into a fight you were not willing to make. At a 1967 Hall of Flowers conference in Golden Gate Park on the white response to Black Power, Panther founder Bobby Seale and Revolutionary Communist Party founder Bob Avakian were handing out flyers. I don’t recall what Seale’s said, but Avakian’s said, quoting as best I remember: The time is not right for us to join our Black Brothers on the rooftops with rifles, but we can raise money to help them get the guns they need. I told Bobby Seale, “That’s some program – let’s you and him fight! You guys kill each other and we’ll watch!”

Later, after her breakup with Castro, Sara was involved in efforts to expose the drugs-for-money scandals known as Iran-Contra. Iran-Contra was a CIA operation during the Reagan Administration to sell weapons to Iran despite an arms embargo, using the money to secretly fund Contra military operations against the Sandinista government in Nicaragua. Large-scale drug smuggling to the Bay Area was involved, with money going back to the Contras. Eventually fourteen government officials, including Secretary of Defense Casper Weinberger, were indicted and eleven convicted. Some won appeals, and the rest were later pardoned by President George H.W. Bush.

According to a deeply-researched story in the San Jose Mercury-News published on August 18, 1996:

For the better part of a decade, a San Francisco Bay Area drug ring sold tons of cocaine to the Crips and Bloods street gangs of Los Angeles and funneled millions in drug profits to a Latin American guerrilla army run by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, a Mercury News investigation has found. This drug network opened the first pipeline between Colombia’s cocaine cartels and the black neighborhoods of Los Angeles, a city now known as the “crack” capital of the world. The cocaine that flooded in helped spark a crack explosion in urban America . . . .

But that was all in the future, after Dave and Sara went their separate ways. For now, it was about enjoying the sun peeking through the fog along the coast, enjoying domesticity, solving the world’s problems with me over glasses of red wine, and thinking about writing that great novel he still believed he had in him, the one that would spark The Revolution

Looking for The Lost Dutchman

Umpteenth of Remember, 1965

Dear Creditor:

For thirty years I wandered, not knowing who I was: a sleazy, mind-bare amnesiac. But now I know: a poet, red, rare, flaming, to take back your Cadillac, your chains of dreams that I no longer trip to – and your lousy pink slip, too.

Unscrew you, and that other frightful excrescence, your Madison Avenue planned obsolescence I did duly crave.

Yours truly,

Dave

P.S. I have entered as a partner in the firm of Daredmuch and Didmore. — David Castro

In 1967 union colleague Bruce Benner invited me on a backpacking trip to Arizona’s Superstition Mountains, some 50 miles east of Phoenix. Bruce thought he had figured out where gold from the legendary Lost Dutchman Mine could be found. We did everything wrong that trip and found no gold or mine, but we survived – painfully — our own lack of preparedness, and I came out hooked on the legend of the Lost Dutchman, and of putting together the clues in the hundred-year-old puzzle. I returned to the Superstitions over a dozen times during the next thirty-three years, the last in 2000 when I got, for the first and only time, an attack of gold fever. I usually went alone, fasting and detoxing from the alcohol that had become the center of my life. In the Spring of 1972 I invited Dave Castro to accompany me.

Dave had never been backpacking in his life, so it was a brand-new adventure for him. We borrowed equipment and headed to Arizona, armed with several old books on the Lost Dutchman, one of which described a mule trail up Bluff Mountain. Our goal was to find that trail and climb it, and to quit smoking. Both of us were heavy cigarette smokers with coughs, and, we thought, five abstinent days in the wilderness ought to break the habit. Despite that, we both were strong enough to hike the hard trails with water, food, and gear on our backs.

As luck would have it, though, shortly after hoisting our backpacks and setting out on the Dutchman’s Trail, we came across an almost-full pack of Lucky Strikes someone had dropped. So much for abstinence – we would ration those cigarettes out until we returned to civilization and bought more. We ran into a group of young hikers with a .22 rifle who said they were out to hunt the Easter Bunny. We set up camp at Bluff Spring and began exploring, learning quickly that jumping cholla cactus really does attack passers-by! While I followed the spring slowly up towards the base of the mountain, Dave wandered further out, covering a wide swath of potential trailheads, and came back sweating and breathless to tell me, “I think I found it, man!”

The Lost Dutchman Mine legend was related to a group of Mexican prospectors, the Peraltas, who probably worked a mine near Wickenburg and used the Superstitions as a resting place to water their mules in a defensible location against the local Apaches, for whom the mountains were sacred territory. Dave had found it, a clear trail up Bluff Mountain, the rocks worn white from the Peralta’s mules. We followed it to the top to find more evidence, a broken-down dam across an intermittent stream to catch winter and summer rainfall. The gold that the Dutchman and others had found, as Bruce Benner had deduced, had to be partially-milled gold ore from a distant mine that the Apaches dumped on the ground when they attacked and slaughtered the Peralta’s last expedition. The Apaches took the mules, and the leather sacks the ore was carried in, but not the gold ore.

When we returned to our camp we discovered that some of our food had been taken, with a scrawled note saying, “Sorry we were hungry.” The thieves had left us several little white pills. We had no idea what they were, but Dave told me, “Man, I can’t believe I’m passing those up. The old me never would have.” We buried them deep in the sand under rocks.

From all reports, Dave’s clean periods off heroin never lasted. I am reasonably sure he wasn’t using that week we went looking for the Lost Dutchman. Perhaps, like myself with red wine, he could by force of will hold his addiction at bay for awhile, but then it made its claims. I don’t know that he ever considered a recovery program; probably, as with me and alcohol, he thought he was too smart to need help — he could do it alone. Years later, in 1983 and after a thousand false starts, I stopped drinking with sheer will power. And my addiction went crazy. I saw my marriage and my career collapsing and I was helpless to do anything about it. All my energy went into just not picking up that drink. And when it all fell apart in 1988 I did what I knew how to do for the pain – I got drunk, and then I got help. I couldn’t do it alone.

Back at our Bluff Spring campsite we were thrilled with our discoveries even as we picked cholla spines out of our boots. Dave was even more excited than me, slapping me on the back saying, “We did it, man, we really did it!” He couldn’t wait to tell Sara; he had earned his backpacking chops, he had made a real contribution to my quest for the Lost Dutchman. He was an honest-to-God explorer, a real Desert Rat! Ever the romantic, on the hard hike back Dave lagged behind fashioning a bouquet of cactus and spring blossoms to bring home to Sara.

In the glowing aftermath of our successful ordeal, we decided to become businessmen. I think the idea was Dave’s, who had been okay with his first time eating the dried foods we brought and cooked. We would create one-day supplies of freeze-dried organic food for backpackers and call it Day Tripper Food Packs. Instant oatmeal and dried fruit for breakfast, a protein bar and dried fruit for lunch, a stew mix of protein bar, dried veggies and noodles for dinner. We named ourselves Owl and Butterfly and Dave had labels made up with that design for the brown paper bags we would put them in.

We went to the local Santa Cruz natural foods market to pitch our product and get supplies and the owner agreed to try it out. I think we made about a dozen Owl and Butterfly Day Tripper Food Packs and set them out on display. One of us would check back every couple of days, but they seemed to move very slowly. One day the owner told us a customer had come in complaining they were “inedible.” He asked us to remove the remaining bags and paid us the few bucks he owed us. Here we were, a union pie-card and an anarchist revolutionary, failures as capitalist plutocrats!

- Death of a Junkie

Topsy —

Sing a song of sixth sense

Catcher in the Rye

Four and twenty Muslims

Ravens on the fly

Miles go Bye Bye Blackbird

Take a hike Jim Crow

The seeds of topsy-turvy

Are blossoming you know… ~ David Castro

Spurred by Elaine’s decision to enroll at San Francisco State University to become a nurse, we moved back to San Francisco in early 1974. The Lipton Tea organizing having fizzled out, I now drove to Salinas for two days a week to take care of union business. With Santa Cruz no longer on my agenda, and with drinking taking up more and more of my non-working life, I lost touch with Dave. I worked mainly out of the San Francisco headquarters of ILWU Local 6, and organized throughout Northern California. Later that year I ran for business agent in the Local 6 elections, and won.

In late 1976, Dave Castro showed up at the Local 6 offices with a young woman in tow, Paula Castro (her name from a defunct marriage), who said she was on methadone maintenance for heroin addiction. Dave and Paula met years before in San Francisco’s Bernal Heights neighborhood when Dave, visiting a man he often shot up with, was told that the noise next door was a druggie beating the crap out of his girlfriend, Paula Castro. Instantly furious, Dave kicked in the neighbor’s door and shouted, “No one hurts a Castro!”

I took them to our corner bar/restaurant hangout for lunch. Dave wanted to know if I could get them jobs. He nodded off several times while we were talking, and it was clear that he was back shooting junk. Paula looked embarrassed for him. I told Dave he was not welcome in my house while he was using, that I didn’t want my kids exposed to him, and that I didn’t want him around me or the union. I gave them $20 and said goodbye. That was the last time I saw Dave Castro.

Perhaps it was seeing my own alcohol demons reflected back from him, an ego-driven false superiority, that caused me to end our friendship. I had cast a fair number of people out of my life over 30 years of drinking and my sobriety was still a dozen years away. But in doing so I missed a chapter that I know from my own experience is well worth knowing. In 1978 Paula gave birth to Dave’s child, a daughter they named Stephanie. Her second child, Dave’s first and only.

Trying to be a responsible father, Dave cleaned up and went to the Local 6 hiring hall looking for work. There are certain companies that called where the work was well-known to be hard and the hiring hall regulars often passed those up. One of those was B.R. Funsten. a flooring company in the city located, ironically, near the Hall of Justice, and Dave went to work there. He did well and passed the 90-day probationary period, earning needed health care benefits for his family along with decent wages.

Dionne Castro, Paula’s daughter from an earlier relationship, was seven years old when Dave and Paula lived together. She remembers Dave taking her for a ride in his old sports car, sitting her on his lap, and letting her steer all the way across the Bay Bridge. She also remembers when Stephanie was born, that they went to a liquor store and Dave came out with two bottles that proclaimed, It’s A Girl! Dave dug out an old Royal typewriter that his grandmother had used to write a book and designated it as his inheritance for his daughter.

He broke his leg in a motorcycle accident and Charles McClain was sent by Local 6 to replace him. When Dave returned to work Charley was kept on; they became friends and would meet after work from time-to-time to have drinks at local bars. Charley suspected Dave might have been chipping, using heroin recreationally, but he showed up for work, did his job and stayed out of trouble.

At home, however, there was increasing trouble. Fights, perhaps instigated by Paula’s short temper, became commonplace and sometimes got physical. It was ironic that Dave, who had rescued Paula from male violence, was now committing that same violence. It finally reached the point where Dave wrote Paula a letter saying, “I love you, but I can’t live like this.” Yet he stayed for the sake of his daughter.

I continued my annual backpacking detoxes and in Spring of 1979 I headed to Arizona yet again; on returning home Elaine had some newspaper clippings for me. The April 11 San Francisco Chronicle’s front page story was headed Bloody S.F. Ambush—Drug Agents Shot. The S.F. Examiner’s page 4 article began: Drug shootout: a hunt for middle-level dealers.

In a drug sting gone bad, the stories read, David Castro, 46, had been shot “at least three times” at the corner of 25th Street and Orange Alley. Drug Enforcement Administration undercover agents Salvador Dijamco and Wallace Tanaka, and suspected drug dealer Bernard Altamirano, were wounded. Unarmed and handcuffed, Dave Castro bled out and died in the Mission District alley. Another dead junkie. His daughter was ten months old

Self-Defense or Execution?

–Turvy

…Sing a song of sixth sense

Kiddin’ on the square

Sense the swirly Movement

Dancing in the air

Hark! the scraggly scrum-bums

Marching as they sing

The seeds of topsy-turvy

Will bear Strange Fruit in Spring. ~ David Castro

The official version, according to the two DEA agents who survived their wounds, as did the alleged drug dealer, Bernard Altamirano, was that they were making a fourth heroin buy from Altamirano, with $22,500 in their car. Dave Castro was seen “lurking in the shadows.”

The agents activated a hidden signal to contact four more DEA agents and four San Francisco Police officers staked out a half-block away. Altamirano got into the back seat of the agents’ Pontiac Trans-Am, pulled a gun and ordered them to put their hands on the dashboard. He shot Tanaka in the head, then shot him twice more and shot Dijamco under the arm. Despite three gunshot wounds, Tanaka managed to tangle with Altamirano and Dijamco got out his gun and shot Altamirano in the head.

Dave Castro, the agents said, then came over to the car and reached through a window to try to choke Dijamco. Dijamco shot Castro four times in the head and chest, and then shot Altamirano again.

According to a press report, a passerby, Charles McClain, saw Dave handcuffed and dead on the ground and said, “I know that guy. That’s Dave Castro.” Charles has told me since that Dave, a co-worker at B.R. Funsten, had invited him to meet for after-work drinks at Clooney’s Pub on the corner of 25th and Valencia Streets, less than a half-block from the scene of the killing.

Charley and Dave had met after work from time-to-time and gotten friendly, if not close. Dave never mentioned his family. Charley told me that Dave didn’t show up that evening. He waited, had a drink, then left to see flashing police car lights and a commotion just down the block. He went to investigate, recognized Dave and was asked inside the yellow tape line to make the identification. The police inspector told Charley, “I hope you have a strong stomach.”

The DEA said it was an “out-and-out ripoff” attempt during the federal agency’s effort to “crack a major heroin trafficking network.” Bernard Altamirano was quickly convicted on multiple counts of heroin distribution, assault on a federal officer with a deadly weapon, and being an ex-felon in possession of a firearm. He was sentenced to thirty years in prison and a $15,000 fine. His appeal the following summer was turned down by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.

Altamirano’s version of the fatal event, according to the Appeals Court, differed markedly from the DEA’s:

Appellant’s version of the events which he presented through his own testimony is that the 1978 sales were in fact made by (Gerald) Spendler, the informer, and that his apartment was loaned to Spendler in exchange for small amounts of heroin for appellant’s own use. He explained that Spendler was afraid of Tanaka and had cautioned appellant always to placate him…Appellant also utilized his alleged fear of Tanaka in explaining his agreement to sell $22,500 worth of heroin on April 10, 1979. His version was that when he heard that Spendler had died in early April, 1979, he became even more afraid of Tanaka because he suspected Tanaka was responsible for Spendler’s death.

With respect to the alley shooting, appellant contended he had no heroin with him when he got into the agents’ car, a fact not disputed by the government, and also no .38 revolver, an assertion vigorously contested by the government. As appellant told it, Dijamco saw Castro approaching the car and shot him, at which point appellant attempted to take Dijamco’s gun. During the struggle there were additional shots that wounded both Tanaka and appellant. Castro was merely an innocent bystander killed by an officer with too quick a trigger finger according to the appellant.

The following week, in the Local 6 hiring hall where the three West Bay business agents rotated weekly as job dispatcher, I was approached by Billy S. Billy – not his real name – kept his dues current and worked out of the hall just enough to support other activities. I knew that Billy and Dave were acquainted, and I let him into the “cage” where dispatchers answering phones and writing job orders could be observed by members waiting for work.

Billy told me, “That stuff in the papers about Dave, man, it didn’t go down like they said. They snuffed him, man, pure and simple. I knew Dave, man, we used to chip together.” He went on to weave an elaborate tale: Dave Castro had been busted for possession of heroin. He was let go after agreeing to sell confiscated cocaine for the arresting agents. Billy thought that was Salvador Dijamco, whose street name was Jimmy Rios, and his partner, Wallace Tanaka. Dave, he said, thought he was smarter than the agents and began skimming from the proceeds. Dijamco and Tanaka figured it out and set up the April 10 drug deal to blow Dave away. “Look, man,” Billy said, “Dave didn’t even have a gun. They handcuffed him before they shot him, man, they executed him!”

That sent me on a mission to try and find the truth. I owed Dave Castro’s memory at least that.

While I read a lot of private eye novels, I had no idea how to actually investigate something like this. I enlisted the help of the late Paul Shinoff, a San Francisco Examiner reporter sympathetic to labor, and we set out to find the truth about the death of Dave Castro. Paul dug into available records and went after those that were not made public.

I found myself talking to people I hadn’t even known existed, the hidden underclass of drug addicts and dealers. I waited in a Bernal Heights shooting gallery to talk to one woman while she fixed; she had lived with Dave for awhile. She thought that Dave was dealing on the streets for crooked cops, but had no first-hand knowledge. There were reports of gifts from Dave of grams of cocaine.

Ultimately we gave up. It seemed like Billy’s version was substantially correct, but it was all He said, She said; we had no way to prove it, no hard evidence

Connections…?

(There is) a wealth of evidence that indicts the entire power structure for criminal conspiracy that is of vital importance; it demonstrates the urgency, the terrible and immediate need for change in the United States today, if there is ever to be a tomorrow for mankind.

There’s still time, Brother. ~David Castro

While both Salvador Dijamco and Wallace Tanaka were awarded “purple hearts” by the Drug Enforcement Administration, investigative reporters have, since Iran-Contra, linked the DEA to CIA drug dealing and assassinations. According to Douglas Valentine’s lengthy article in the September 11, 2015, online muckraking journal Counterpunch, the DEA’s Special Operations Group (DEASOG) carried out assassinations of alleged drug dealers in Latin America in the 1970s. In 2012 DEA agents shot and killed alleged drug traffickers in Honduras, including two pregnant women. The DEA later lied to Congress about being fired on first. Valentine described the work of DEASOG:

The job was tracking down, kidnapping, and, if they resisted, killing drug traffickers. Kidnapped targets were incapacitated by drugs and dumped in the U.S. As DEA Agent Gerry Carey recalled, “We’d get a call that there was ‘a present’ waiting for us on the corner of 116th Street and Sixth Avenue. We’d go there and find some guy, who’d been indicted in the Eastern District of New York, handcuffed to a telephone pole. We’d take him to a safe house for questioning and, if possible, turn him into an informer. Sometimes we’d have him in custody for months….”

Lou Conein, who reported directly to CIA head William Colby, created DEASOG specifically to do Phoenix program-style jobs overseas: the type where a paramilitary officer breaks into a trafficker’s house, takes his drugs, and slits his throat. (They) were to operate overseas where they would target traffickers the police couldn’t reach, like a prime minister’s son or the police chief in Acapulco if he was the local drug boss. If they couldn’t assassinate the target, they would bomb his labs or use psychological warfare to make him look like he was a DEA informant, so his own people would kill him.

It is clear that the DEA culture was to operate outside the law with impunity, and murder was a part of their job. That unarmed Dave Castro was shot four times by Salvador Dijamco while co-agent Wallace Tanaka never drew his weapon leaves questions in the air. That a street-wise drug dealer, Bernard Altamirano, would get into a car alone with two buyers he had to presume were also armed, leaving his unarmed backup “lurking in the shadows,” defies logic.

That Dave Castro was handcuffed, and whether it was before or after his shooting is disputed, compounds those questions. That eight other armed officers were just a half-block away and had been signaled but missed all the action is pushing the limits of credibility. And since heroin was always Dave’s drug of choice, how was it he giving people free cocaine?

And would an unarmed junkie backup not be more likely to save his own skin once the shooting started rather than join the fray? If Dave knew who the buyers were or recognized the DEA agents, wouldn’t he have been even more likely to run away? Drug addicts jonesing for their next fix are not known for loyalty, especially to people being shot at by law enforcement. If Dave was part of a high-risk plan to rip-off the DEA agents, why had he invited co-worker Charles McClain for after-work drinks that same Tuesday evening?

Is it just possible that the drug deal, which the Chronicle termed “an attempt to crack a major heroin trafficking network and to reach the group’s major supplier,” links the DEA agents to what became the “drugs for guns” scandals made public a few short years later? A DEA report dated February 6, 1984, showed U.S. law enforcement in 1976 tracking a large-scale cocaine trafficker, Norwin Meneses, an associate of Nicaraguan dictator Somoza who was ousted by the Sandinistas in 1979. Meneses left Managua for California in 1979.

And how much of a stretch is it to connect Manila-born Salvador Dijamco to Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte’s War on Drugs that has murdered thousands of people? The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) maintains an office in Manila and liaisons with the Philippines Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA). The U.S. Government gives Philippines law enforcement millions of dollars each year. The U.S. DEA has been training foreign law enforcement drug agents since 1969, with over 14,000 participants from 94 countries in 2013 alone.

Several plausible scenarios suggest themselves: In exchange for staying out of jail, which might be a federal prison far from home, Dave Castro was dealing coke for crooked DEA agents and skimming to support himself and his family, but he had nothing to do with the Altamirano drug sting and was simply on his way to meet his co-worker for drinks. Walking up 25th Street Dave recognized the agents’ car, or them, and went “lurking in the shadows” to avoid being seen. When the shooting started inside the car, and that’s assuming it was before Dave was shot, he approached the car, was recognized by the DEA agents, and shot. That he was the “innocent bystander” Bernard Altamirano testified to.

Or, the drug deal was set up specifically to kill Dave, who was just a lookout for Altamirano while a supposedly simple exchange was being made in the car, figuring he could help his fellow druggie and then meet his co-worker for drinks. That both DEA agents and Altamirano said there was no heroin present does not make it so. But why would Dave, a smart and street-wise guy, knowingly participate in a rip-off of federal agents who knew who he was?

Salvador Dijamco retired from a 26-year career in the DEA in 1999, and died in Florida 18 years later at age 73. He had numerous awards on his wall, including one from the International Narcotic Officers Association. Wallace Tanaka’s legacy seems to be having had to repay the government $269 for unauthorized expenses he wrongfully claimed reimbursement for in 1977. DEA Records Management Chief Katherine Myrick declared my FOIA request “complex (with) unusual circumstances” and could not say how long it would be for a response. The San Francisco Police Dept. said their records from that period may have been destroyed.

In the 1990s, sober and in a second marriage, I lived in a San Francisco Mission District flat whose back door opened onto Orange Alley, just in from 24th Street, less than a block from where Dave Castro was gunned down. For the ten years I lived there, each year on April 10 I posted flyers telling what I knew of Dave’s story to any who cared to read it. Perhaps it was, on some unconscious level, my recovery program kicking in, making amends for having banished him from my life.

Dave Castro’s ashes were interred at San Bruno’s Golden Gate National Cemetery, next to his parents’ graves. Only three people came to say goodbye. But for all his addiction, his romantic ideas of revolution, his crimes, and his inability to maintain a relationship with women, Dave Castro was as worthy of his story, or his multiple stories, being told as any of us. He was my friend, and while it was a surprise that the Dave Castro I knew was not the same Dave Castro that others knew, that does not devalue the friendship we had

R.I.P.

We resent the credibility gap that divides the acts of those in power from the citizens affected by those acts. Unless understanding, dignity and purpose are restored to the many millions whose lives and work constitute the real society, one of the triumphs of history will be turned into defeat. ~ David Castro

“There are no truths, only stories.” So wrote the Native Canadian author Thomas King, “We know who we are through our stories.” I learned the validity of that when writing a scholarly biography of my communist father. My younger sister, Karen, read a draft and told me, “You missed Dad’s sense of humor.” I thought about that: the only memory that came up was of my father telling me, “Junior, I defended you today. So and so said you weren’t fit to sleep with the pigs, but I defended you. I told him you were fit to sleep with the pigs!” Ha ha, Dad.

So what we have are many different stories, and they are all true, all worth hearing. No one’s version is more right or wrong than anyone else’s, just different. Balance is the closest to objectivity we can really come. Balance can give us the subject as a complex human being in a complicated world, and not a one-dimensional stereotype fitting our preconceptions or prejudices. And we never get it all.

Stories require context. People do not arrive on the scene full-blown, out of the blue. We are all products of our genetics, our environment, our times; they shape us and point us in the directions we take. To understand Dave Castro it is necessary to look at the Sixties and Seventies, at addiction and prison culture, at larger and seemingly unrelated events, and at connections that may not be obvious. So stories, as here, must sometimes digress to embrace a larger scope in order to comprehend the events and actions of one individual.

The revulsion I feel today towards those playing at violent revolution and at police shooting unarmed African Americans felt somewhat different in those turbulent times when cops and radicals were killing each other; when Chicago police broke heads at the 1968 Democratic Convention; when reformers like Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy, and perceived Establishment threats like Malcolm X, were cut down by assassin’s bullets; when urban ghettoes exploded in justified rage; when the Weather Underground tried to manufacture rage with window-smashing and bombs; when American National Guardsmen shot and killed American students at Kent State University, when even pop music was polarized between Ballad of the Green Berets and Eve of Destruction – all set against the backdrop of a deadly war in Vietnam, and the corrupt presidencies of Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon.

In researching Dave Castro’s story there was a lot I didn’t get, couldn’t get, and it often took me in unexpected directions. That is one of the joys and frustrations of research. Trying to get prison records and police reports, aging memories, the unwillingness of important sources to share memories, the passing of others, the continuing secrecy about CIA-DEA drug dealing and assassinations – all of these put serious limits on my research. I could only go with what I had, and even then, there had to be some selectivity to avoid embarrassing innocent people.

One of the difficulties was in trying to get DEA and SFPD records. History, it is often said, is written by the victors. I am not a person who sees conspiracy behind every wrongdoing, but as in Colombian writer Juan Gabriel Vásquez’s remarkable novel, The Shape of Ruins, control, collusion and cover-up – words in current American headlines – have always come easily to those with power. In assembling Dave Castro’s story, I tried to connect the dots, using educated guessing where some of the blanks were.

Some remember Dave Castro with anger, others with affection. Celia Rosebury Lighthill says: “He had a fine mind and a quick wit, and he was indispensible to me in the early days of Insurgent.” Elaine Millán recalls Dave as a “brilliant-minded recovering addict who was progressive, was a talented writer and attracted fabulous, dynamic women as partners.” Maria Perez remembers Dave as a child-loving man who played happily with her when she was a child. Dionne Castro Joyeux remembers from her childhood that Dave was “a good guy, always nice to me.” Others said he had “no patience” for being a father and was “never around.”

Stephen Lighthill appreciated Dave’s understanding of the financial pressures on him at ADF, and that he was always “respectful.” Mike Myerson, a political activist who is not easily conned, worked at ADF for awhile and recalls Dave Castro as “:idealistic and romantic, charming, funny, bright…and a hustler.” While it was sometimes hard to tell fact from fiction with Dave, “he was an honest guy and always straight with me.” Deanne Burke said Dave was “narcissistic and complicated…an explosion of personality, of darkness and light.” But, she adds, “he had life-long neighborhood friends who loved him.” Several people who closely shared some of Dave’s life during the years we were friends chose to remain silent. Dave called himself a “professional dirty guy.” They are all right.

Re-reading this, there are a number of possible takeaways I see: 1) Who cares? 2) Castro was a bad guy and got what he deserved. 3) Hey, play with fire and you get burned. 4) Cautionary tale about addictions and their delusions. 4) Dave was a wounded soul with an addict’s insistent but fragile ego looking for love and attention and not knowing how to really love back. 5) Dave was a poet and a lover, dreaming the Romance of The Revolution. 6) A rebel against injustice and power, from his father to prisons, capitalism and The System, misguided perhaps, but idealistic. 7) Sociopath. 8) All of these, and more – complex and contradictory, and all too human.

For me, he was smart but made some dumb decisions; street-wise but full of romantic visions; he was gentle and fierce, idealistic and cynical, hardened and vulnerable, narcissistic and charismatic. He was a junkie, criminal, and con artist, an outlaw at heart, but also a poet, a lover, a pal, a rebel with a cause. At different times of my life I was some of those myself. Low self-esteem is often a hallmark of addiction that leads people like Dave, and me, to over-achieve, to get attention, to win approval, knowing inside that we were really frauds, unworthy of the approval we demanded, the love we craved but were unable to accept or to give back.

When I first got sober I heard people saying that alcoholism and addiction were a fatal disease. I thought that was hyperbole to scare us newcomers straight. The longer I am sober, though, the more I see the truth of it. It may not go on death certificates as drug overdose, or liver failure while lying in the gutter, but as auto accidents, suicide, cancer, heart attack, or foolishly doing dangerous things as a way of shouting, Look At Me, I Matter! Or getting shot down in an alley.

But I was a lucky one. I have my scars, but lived on to change and become who I am today, to leave Al behind and become Albert, a whole person. Dave Castro was denied that opportunity.

Whichever Dave Castro those who knew him might remember, and whatever opinion you, the reader, may form after reading this, I hope we can all agree that he should not have died the way he did. And that, if the still-secret facts show a deliberate murder, those responsible, living or dead, should be held accountable. My friend in recovery Ellen S. adds from her father: “Take the wheat with the chaff in the palm of your hand; and with the gentle breath of friendship, blow the chaff away.”

The night Jerry Stoll called Sally Pugh to tell her that Dave Castro was dead, she had a dream: Dave appeared and said to her, “I just want you to know I’m okay.” R.I.P. David, Rest in Peace. Maybe I’ll be seeing you soon.

Silent Generation

Silently the silent generation waits

abandoning hypocrisy and slick suburban ways

conning the futility of passion

the lurking lie within great truth

the chains of universal salvation

fall rusted from their uncommitted feet.

Sing them not the glory of old glory

nor the Alger bliss of western enterprise;

they see disillusion fading pensioned eyes

and smell degradation.

Waywardly the wayside generation waits

for gutted hulks to smash on rocks of greed

with involuted power gone mad with fear

that chews and grinds and spews itself:

the fate of rotting ships of state.

Silently the silent generation waits.

Sing them not the glory of old glory

nor the Alger bliss of western enterprise;

the greed that feeds on truth and spits out lies

starves in their silence. ~ David Castro

Thanks to all who dug into their memories and shared stories with me. I could not have done this without you. Those who stayed silent: I remain grateful to have known you at a time when Dave was alive and happy.