A man who allegedly sold “the best quality crystal meth” in Bisbee will be in court Thursday for a hearing on whether the Cochise County Attorney’s Office must disclose the name of any confidential informants involved in the case.

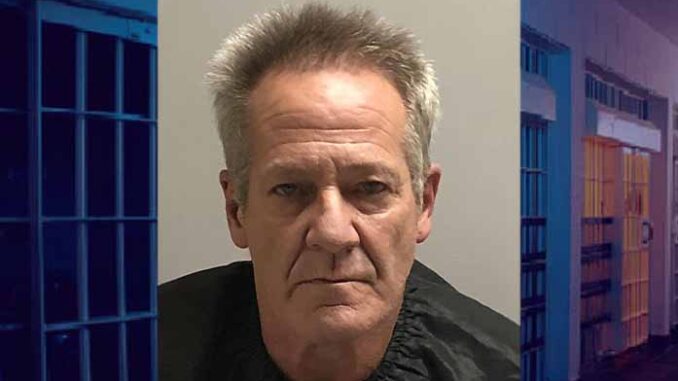

David Leroy Adams was indicted in November 2020 on felony charges of selling methamphetamine from inside his home and possession of six firearms during a felony drug offense. He is also charged with child abuse and endangerment for keeping nearly one pound of meth in the house.

Defense attorney Nicholas Brereton has asked Judge Timothy Dickerson to grant a motion to suppress self-incriminating statements Adams made after his arrest. The judge will also have to decide at Thursday’s hearing whether to compel prosecutor Dan Akers to reveal the name of any informant who took part in videotaped drugs deals with Adams.

Among the issues for Dickerson to consider is the fact Adams, 59, is not charged with any drug deals. Instead, the grand jury indictment simply charges Adams with possession of a dangerous drug for sale after a search turned up a large amount of meth in a kitchen cabinet and more of the drug in an outbuilding.

Court records show at least one informant worked with investigators from Bisbee PD and the DEA who had Adams’ home under surveillance for several months in 2020. The name of that informant or any others has not been revealed by investigators nor the prosecutor, despite a written demand by Brereton.

“Who was the informant? Was this informant reliable? What was the informant’s opportunity to observe, his knowledge of what might constitute illegal drugs, his biases and relationship with David Adams?” Brereton’s motion to compel reads. “The answer to those and other questions regarding the informant and the overall circumstances of the informant’s work with and for the officers are important in order to establish the facts” of the case.

“There is no danger to anyone posed by disclosure in this case, and the Defendant’s fundamental rights of due process—protected by both the Arizona and the United States Constitution–would be violated if disclosure is not made,” he further argues in the motion. “Failure to disclose the informant would deprive Mr. Adams of a fair trial.”

In response, Akers of the Cochise County Attorney’s Office acknowledged that if Adams was charged with conducting a drug sale with an informant then “the informant’s identity must be disclosed.” But there is no informant who is a witness to the facts upon which the possession charge against Adams is based, he wrote.

Akers also notes that prosecutors “almost never voluntarily discloses the identity of confidential informants, and courts only rarely order prosecutors to do so.”

Such disclosure, Akers argues, “would expose the informant to danger from others in the ‘drug world’ and would compromise the ability of law enforcement to recruit future informants, since it would weaken their ability to legitimately promise a potential informant that his or her identity would never be disclosed (thus insuring his or her safety).”

Dickerson will also have to decide Thursday whether to declare any of Adams’ post-Miranda statements to have been involuntarily made as the result of “psychological coercion” by investigators.

According to the motion to suppress, questioning of Adams occurred following his release from a local hospital after he was transported from the Cochise County jail for complaints of chest pains and difficulty breathing. After being medically cleared to return to the jail, Adams initially told investigators he had no knowledge of the meth found in his home.

Adams later claimed he was “holding” about one point of meth in a kitchen cabinet for a dealer named Toby Jones. He also reportedly admitted selling the drug himself; a smaller amount of the drug was seized in a garage-like shed on Adams’ property.

But according to Brereton, Adams “wanted the questioning to stop and maintains that anything he said was merely what the officers wanted to hear. Further, Mr. Adams was fearful that he would have another heart-related episode similar to that which he’d experienced at the time of his arrest.”

Akers’ response pushes back on claims that Adams was somehow coerced by investigators during the videotaped interview that lasted less than an hour with two breaks. .

“He was provided with food and water during the interview,” Akers wrote. “He did not complain of any serious medical issue at any time in the interview. He did not complain at any time that he felt coerced. He appears alert, responsive, and completely normal – even cheerful at times – throughout the video footage of the interview.”

If convicted of all counts, Adams faces a prison sentence which “is tantamount to a life term” due to his age, Brereton argues.