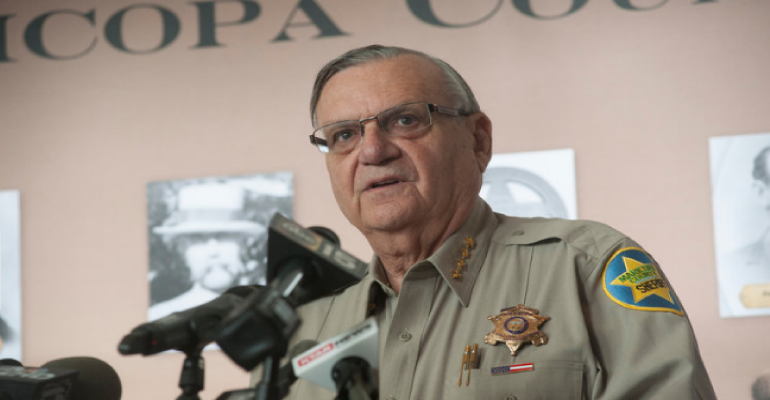

Federal Judge Murray Snow on Friday referred to another judge the case against Maricopa County Sheriff Joe Arpaio, top deputy, Jerry Sheridan, Capt. Steve Bailey and former Arpaio attorney, Michele Iafrate, to decide whether to pursue criminal charges. Judge Snow found that there was probable cause that Arpaio ignored court orders in a racial profiling case.

The judge’s ruling reads in part:

Based on the extensive testimony set forth at the hearing, the Court has already concluded under the civil standard of proof that Sheriff Arpaio knew of the December 2011 preliminary injunction and intentionally disobeyed it.

In brief summary, in December 2011, still well prior to trial, this Court entered a preliminary injunction prohibiting the Defendants from enforcing federal civil immigration law or from detaining persons they believed to be in the country without authorization but against whom they had no state charges. It also ordered that the mere fact that someone was in the country without authorization did not provide, without more facts, reasonable suspicion or probable cause to believe that such a person had violated state law.

Sheriff Arpaio admitted that he knew about the preliminary injunction upon its issuance and thereafter. Sheriff Arpaio’s attorney stated to the press that the Sheriff disagreed with the Order and would appeal it, but would also comply with it in the meantime.

Sheriff Arpaio’s attorney and members of his command staff repeatedly advised him on what was necessary to comply with the Order. However, the Court found that Sheriff Arpaio intentionally did nothing to implement that Order. The MCSO continued to stop and\detain persons based on factors including their race, and frequently arrested and delivered such persons to ICE when there were no state charges to bring against them. Sheriff Arpaio did so based on the notoriety he received for, and the campaign donations he received because of, his immigration enforcement activity.

Since Sheriff Arpaio had previously taken some of his arrestees to the Border Patrol when ICE refused to take them, he determined that referral to the Border Patrol would serve as his “back-up” plan for all similar circumstances going forward. Sheriff Arpaio’s failure to comply with the preliminary injunction continued even after the Sheriff’s appeal to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals was denied months later. When Plaintiffs accused Sheriff Arpaio of violating the Order, he falsely told his lawyers that he had been directed by federal agencies to turn over persons whom he had stopped but for whom he had no state charges. Nevertheless, Sheriff Arpaio’s lawyer still advised him that he was likely operating in violation of the preliminary injunction. Although Sheriff Arpaio told counsel on multiple occasions either that the MCSO was operating in compliance with the Order, or that he would revise his practices so that the MCSO was operating in compliance with the Order, he continued to direct his deputies to arrest and deliver unauthorized persons to ICE or the Border Patrol.

It has not been possible for the MCSO to track the number of persons who were stopped or arrested because of Sheriff Arpaio’s violation of this Order over the ensuing 17-months that it was ignored.

Throughout this case, the Court has reminded Sheriff Arpaio that he is the party to this lawsuit, not his subordinates, and thus the failure of his subordinates to carry out this Court’s orders would amount to his own failure to do so.

When Sheriff Arpaio gave his April 23, 2015 testimony on the Montgomery investigation, he testified that the MCSO possessed some documents and materials pertaining to it. To assign personal responsibility for the preservation and production of such materials, including all electronic data, the Court ordered the Sheriff to personally take charge of preserving, retrieving and disclosing the documents.

Despite this Court’s order that Sheriff Arpaio personally direct compliance with this Court’s preservation and production orders with regard to the Montgomery materials, the Sheriff failed to do so. He subsequently testified that he “wasn’t personally involved” with this Court’s order regarding the preservation and the production of the Montgomery materials and that he did not recall having any discussion with anyone about the order.

There is probable cause to believe that the Sheriff intentionally failed to produce all of the documents he had in response to this Court’s order. Specifically, at the time the Court issued the above order, the Sheriff knew that Montgomery had given the MCSO 50 hard drives that Montgomery claimed to be the master database of records that he had supposedly purloined from the CIA.

To reveal those hard drives would have revealed that they did not contain the materials that Montgomery had described. It also may have called into question some of Sheriff Arpaio’s other ongoing investigative activities in which he had partnered with Montgomery, such as the alleged illegitimacy of President Barack Obama’s birth certificate. It would also reveal that the MCSO actually took possession of, and intended to use, material that it believed to have been stolen from the CIA.

Neither Sheriff Arpaio nor anyone else at the MCSO disclosed the hard drives in response to this Court’s order or the Monitor’s subsequent follow-up ITRs. Only months later, during the July 2015 site visit, did the Monitor independently discover the existence of the hard drives, which had been placed in a locker in the property and evidence department under a Departmental Report number designed to shield their disclosure.

This failure to produce the 50 hard drives violates this Court’s April 23, 2015 directive requiring such production. It further violates orders requiring the Sheriff and the MCSO to comply with all document requests made by the Monitor as well as the directive that the Sheriff cooperate with the Monitor and withhold no information from him.

The Sheriff now claims that he “wasn’t personally involved” in implementing the Court’s order. The circumstances provide probable cause to believe otherwise. Even if it were as the Sheriff claims, however, the Sheriff still violated this Court’s orders to personally direct the preservation and production of all such documents.

Perjury is a crime. So is a false declaration to the court. Perjury can also provide a separate basis for a criminal contempt charge, but only when it results in an actual obstruction or attempt at obstruction of justice.

The law also requires that even false testimony given in an attempt to obstruct justice cannot provide the basis for a separate criminal contempt charge unless “from the testimony itself it is apparent that there is a refusal to give information which in the nature of things the witness should know.”

This Court has found, under the civil standard of proof, that Sheriff Arpaio and Chief Deputy Sheridan intentionally made a number of false statements under oath. There is also probable cause to believe that many if not all of the statements were made in an attempt to obstruct any inquiry into their further wrongdoing or negligence.

Nevertheless, as expressed above, “the test is not whether the testimony was perjurious or false but whether without the aid of extrinsic evidence the testimony is ‘so plainly inconsistent, so manifestly contradictory, and so conspicuously unbelievable as to make it apparent from the face of the record itself that the witness has deliberately concealed the truth and has given answers which are replies in form only and which, in substance, are as useless as a complete refusal to answer.’”

Although their testimony is internally inconsistent in many respects, the falsity of that testimony is best demonstrated by evidence extrinsic to their own testimony, rather than “from the testimony itself.” Thus, though the false testimony may provide a potential basis for a criminal prosecution, it cannot be separately charged as contemptuous.

As has been more extensively set forth by the Court in its Findings of Fact, (Doc. 1677), Sheriff Arpaio and Chief Deputy Sheridan have a history of obfuscation and subversion of this Court’s orders that is as old as this case and did not stop after they themselves became the subjects of civil contempt.

Almost immediately after the Court entered its original October 2, 2013 injunctive order, (Doc. 606), the Court had to amend and supplement the order and enter further orders because: (1) the Sheriff refused to comply in good faith with the order’s requirement that he engage in community outreach, and (2) the Sheriff and his command staff were mischaracterizing the content of the order to MCSO deputies and to the general public. Both of these revisions increased the duties of the appointed Monitor at the expense of county taxpayers.

Within one month of those revisions, the Defendants disclosed to the Court the arrest, suicide, and subsequent discovery of misconduct of Deputy Ramon “Charley” Armendariz who had been a significant witness at the trial of the underlying matter.

Among other things, the disclosure of Armendariz’s misconduct eventually resulted in the determination that: (1) the Sheriff had not complied with his discovery obligations in the underlying action, (see Doc. 1677 ¶¶ 213–17); (2) that MCSO supervisors had long been aware of Armendariz’s problematic behavior and misconduct and had not appropriately supervised Armendariz and many other deputies; (3) the MCSO was routinely depriving members of the Plaintiff class of their property and retaining it without justification; (4) the Sheriff had done nothing to implement this Court’s 2011 preliminary injunctive order; and (5) the Sheriff was not investigating the allegations of misconduct in good faith—especially those that pertained to him or to members of his command staff.

Sheriff Arpaio and Chief Deputy Sheridan intentionally manipulated the investigations they initiated in response to the misconduct revealed by the Armendariz discovery to engineer pre-determined results, to prevent effective investigations, to cause investigations to be untimely, and to fail to follow up on appropriate allegations. Moreover, the investigations were conducted pursuant to policies that discriminated against the Plaintiff class.)

Although the Monitor pointed out many investigative flaws early on, they were never corrected nor even recognized as flaws. In fact, it was not until November 2014 that the MCSO finally informed the Court that the videotapes found in Armendariz’s garage demonstrated that the MCSO had done nothing to implement this Court’s December 23, 2011 preliminary injunction. Shortly after that discovery, Sheriff Arpaio and Chief Deputy Sheridan, among others, became the subjects of civil contempt proceedings. Thereafter, the Sheriff, Chief Deputy Sheridan, and members of their command staff misstated facts to both the MCSO investigators and those of the Monitor team.

The Court had been aware of some violations of its preliminary injunction in making its May 2013 Order. It did not know until November 2014, however, that the Sheriff had taken no steps to implement that Order.

Despite this Court’s order that the Sheriff keep the Court updated on the initiation and completion of the IA investigations, (Doc. 795 at 17), he did not timely or adequately do so. Further, when Sheriff Arpaio and Chief Deputy Sheridan took the stand during the contempt hearings in April, September, and October 2015, they both gave intentionally false testimony under oath concerning the Montgomery and at least several MCSO internal affairs operations.

As is discussed above, in the period between their April 2015 and September/October 2015 testimony, contrary to the Court’s orders to do so, Sheriff Arpaio provided no direction to the MCSO in the preservation and production of the Montgomery materials and neither he nor Chief Deputy Sheridan disclosed those materials as ordered. Further, in July 2015, when an additional 1459 IDs were discovered, which included many IDs belonging to members of the Plaintiff class, Chief Deputy Sheridan concealed the IDs from the Monitor and ordered that Captain Bailey suspend the relevant IA investigation into them in an attempt to evade this Court’s order requiring disclosure of that IA and the Monitor’s complete access to that investigation.

Chief Deputy Sheridan then made misstatements of fact both to the media and to the Monitor about his actions.

In the face of the above misconduct, Sheriff Arpaio’s proffered list of the steps he has taken over the last three years to comply with this Court’s initial order falls flat as a justification for not initiating a criminal contempt hearing. The Monitor reports that now, nearly three years after the promulgation of that order, the Sheriff is only in compliance with 63% of his Phase I obligations and 40% of his Phase II obligations. (Doc. 1759 at 180.) Further, the Monitor notes that “we continue to find supportive, well-intentioned sworn and civilian personnel in administrative and operation units of MCSO. What is lacking is the steadfast and unequivocal commitment to reform on the part of MCSO’s leadership team—most notably the Sheriff and Chief Deputy.”

The Sheriff promises a new willingness to implement this Court’s orders. (Doc. 1770.) Such assurances are not new, and they have proven hollow in the past. When the Montgomery misconduct was disclosed, the Sheriff represented in response to orders of this Court that he would provide his full cooperation to the Monitor.(Doc. 700 at Tr. 70–73.) He has represented that he would conduct complete and full IA investigations, that he would implement and had been fully implementing this Court’s order, and that he would hold persons responsible for their misconduct no matter how high in the office the investigations took him. He also promised to personally direct the preservation and production of the Montgomery documents. (Doc. 1027 at Tr. 650–60.) He has done none of these things.

As a result of his previously undisclosed and additional misconduct, the Court has recently entered supplementary remedial orders. The Sheriff’s defiance has been at the expense of the Plaintiff class. The remedies are at the expense of the citizens of Maricopa County. Little to no personal consequence results to the Sheriff. As a practical matter, the County indemnifies its officeholders for their civil contempt and the county treasury bears the brunt of the remedy for the Sheriff’s § 1983 violations. While one of the civil remedies imposed by the Court creates an independent disciplinary process to impose the MCSO’s own employee discipline policies in a fair and impartial manner, the Sheriff is an elected official and not an employee of the Sheriff’s office. He is thus not subject to MCSO disciplinary policy or this Court’s civil remedy.

This lack of personal consequence only encourages his continued non-compliance.

Sheriff Arpaio offers to put “‘skin in the game’ consistent with the suggestions discussed in 2015.” (Doc. 1770 at 11.) As the Court observed in response to that 2015 offer, however, payments made by the Sheriff that are funded by the donations of others do not provide the Sheriff with sufficient personal consequence to deter continued misconduct. Further, since the time he made that offer, the Sherriff’s civil contempt has been found to be intentional, and the Sheriff has continued to commit acts of obstruction.

To the extent the Sheriff’s offer could be considered an offer of settlement it should be evaluated by a prosecuting authority.

Sheriff Arpaio may be in charge of the MCSO for the foreseeable future. In doing so, he must follow the law. If this Court had the luxury of merely entering what orders were necessary to cure a one-time obstruction, or if the Sheriff had evidenced a genuine desire to comply with the orders of this Court, it would be a different matter. The Court has exhausted all of its other methods to obtain compliance.

Therefore, in light of the seriousness of this Court’s orders and the extensive evidence demonstrating the Sheriff’s intentional and continuing non-compliance, the Court refers Sheriff Joseph M. Arpaio to another Judge of this Court to determine whether he should be held in criminal contempt for: (1) the violation of this Court’s preliminary injunction of December 23, 2011, (2) failing to disclose all documents that related to the Montgomery investigation in violation of this Court’s specific order entered orally on April 23, 2015, (Doc.1027 at Tr. 625–60), and the Monitor’s follow-up ITRs for this material in violation of this Court’s orders requiring compliance with the Monitor’s requests, (Doc.606 ¶ 145; Doc. 700 at Tr. 71–73; Doc. 795 at 20), and (3) his intentional failure to comply with this Court’s order entered orally on April 23, 2015 that he personally direct the preservation and production of the Montgomery records to the Monitor, (Doc. 1027 at Tr. 625–60).