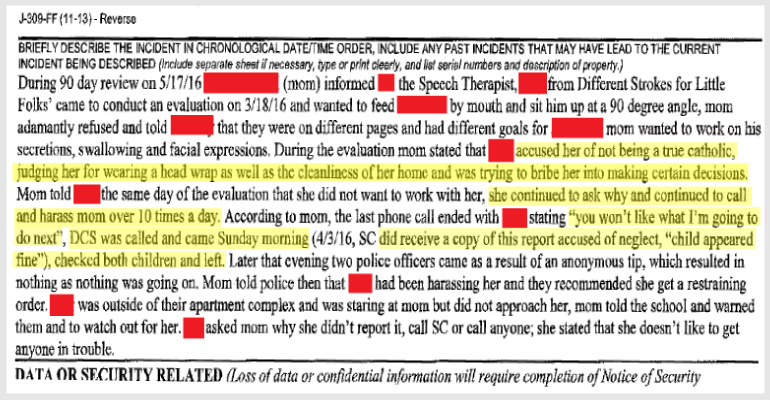

As a handful of Arizona lawmakers appear to be trying to protect the Department of Child Safety, an exchange documented by a DES caseworker brings into sharp focus why those efforts must be scrutinized. A document, recently obtained in a public records request, shows what perils Arizona parents face at the hands of the very welfare agencies tasked with protecting them.

Those people, who have had DCS encounters of the worst kind, will say that the parent referenced above “got lucky.” Because her child has special needs, he would have been too hard to place in a foster home. As a result, some would argue, that the parent and child were never really at risk of losing each other. Those same people would likely claim that because DCS receives federal money for every child placed in foster care, kids, who can easily be placed in foster care, are taken faster and more frequently than others.

Supporters of the DCS status quo would say that the document shows that the system works.

The system is not working, and while the mother in the case above was spared from DCS intervention, too many parents have not been so fortunate. Not only are they stripped of their children, they are stripped of their Constitutional rights in the process.

Reasonable grounds exist

Last week, Rep. Kelly Townsend tried in vain to make her fellow lawmakers understand that Arizona law requires Department of Child Safety (DCS) caseworkers to obtain a warrant or other court order before taking a child away from their parents unless exigent circumstances exist.

Townsend was fighting an effort by Rep John Allen to weaken the protections of Arizona parents by the State’s Constitution. Specifically A.R.S. 8-821; taking into temporary custody; medical examination; placement; interference; violation; classification, which reads in part:

A. A child shall be taken into temporary custody in proceedings to declare a child a temporary ward of the court to protect the child, pursuant to an order of the juvenile court on a petition by an interested person, a peace officer or a child safety worker under oath that reasonable grounds exist to believe that temporary custody is clearly necessary to protect the child from suffering abuse or neglect. If a child is taken into temporary custody pursuant to this section, the child’s sibling shall also be taken into temporary custody only if reasonable grounds independently exist to believe that temporary custody is clearly necessary to protect the child from suffering abuse or neglect.

During floor debate, Rep. Jesus Rubacalva, through questioning of Allen, revealed that DCS had not obtained any warrants or court orders before removing children from their homes. His question forced Allen to end the debate immediately.

The arbitrary nature of it all

Countless families have reported being victims of the arbitrary nature of child seizures by DCS workers. A report prepared by the Arizona Auditor General in 2015, found that the Department’s “has inadequately implemented critical components of its child safety and risk assessment process.”

Those families still have few protections or protectors. Case in point; Townsend is under a gag order. The gag ordered was put in place after Townsend began looking into a case involving two young girls in the Phoenix area taken from their mother by DCS caseworkers.

The Arizona Auditor General’s Office’s report was damaging and confirmed that families need protecting. The report focused on the Arizona Department of Child Safety’s child safety and risk assessment practices and its approach for determining whether to remove a child from their home.

The report found that the Department’s “child safety and risk assessment tool does not sufficiently guide caseworkers in making child safety decisions.” Auditors found that the Department had “inadequately implemented critical components of its child safety and risk assessment process.

The ADI reported on the audit at the time it was released. The article reads in part:

According to the auditors, “The Department’s child safety and risk assessment tool does not sufficiently guide caseworkers in making child safety decisions. Insufficient training has also limited caseworkers’ ability to conduct child safety and risk assessments.”

Auditors found, that although “caseworkers and supervisors should come to these meetings with open minds, some indicated that they come with their decision already made regarding the child – removal decision and may not adequately engage with families during the meeting.”

Auditors concluded that the “Department needs to modify or replace its child safety and risk assessment tool, provide adequate training for caseworkers and supervisors, and improve safety planning.”

If that is not bad enough

In last week’s floor debate, Townsend spoke of a pendulum. She said that authorities go from taking too many children away from their families to not taking enough. Right now, the pendulum appears to be swinging in the direction of too many to many DCS critics.

As Townsend stated, no one wants DCS workers to leave kids in homes with abusers. However, Townsend noted that currently most kids are removed due to allegations of neglect not out-right abuse.

Few people would deny the wisdom of erring on the side of caution, but they would also likely argue that caseworkers need to side with reason before removing a child.

As we have seen, Arizona law demands it:

“A child shall be taken into temporary custody in proceedings to declare a child a temporary ward of the court to protect the child, pursuant to an order of the juvenile court on a petition by an interested person, a peace officer or a child safety worker under oath that reasonable grounds exist…

In the case of 5-year-old, Devani, it does not appear that reasonable grounds did exist. Yet, she was ripped out of her home only to be handed over to sexual predators, and eventually adopted by a mother who nearly burned her to death.

She is now in a Tucson hospital fighting for her life.

Before Devani’s story became public, the public had heard about Octavia Rogers. Rogers, who was using Spice at the time she killed her three kids, had history of abuse and neglect. None of the instances reported would cause any reasonable person to believe that Rogers would kill her kids.

No one could hold the caseworkers responsible for the death of Rogers’ children. However when asked about the DCS reports on Rogers, DCS director Greg McKay claimed in a news interview: “The department has to show to a court that there is imminent danger – exigency. In none of these cases, from 2010 to the 2016 case, did we, as a government agency, have the legal right to take these children away from their mother.”

Since we know that DCS had not obtained one warrant or court order before removing a child last year, McKay either does not know what is happening in his department, or he knows what his obligations are and chooses to ignore them.

He should have simply said there was no way to predict that the pot smoking mom would move to Spice and become a murderer. But he didn’t.

Codifying the failure of DCS

Devani’s story should have been enough to send outrage across the state. Instead, the Ducey administration had Allen offer an amendment that would have legitimized taking kids while denying parents their due process.

Allen’s amendment to Sen. Barto’s DCS oversight bill would have codified the failures of DCS to obtain warrants. Clearly the amendment had been handed to Allen due to the fact that he is one of the governor’s go-to-guys in the Legislature.

It was clear from the floor debate that Allen had no idea what his amendment was all about. The truth be told: only someone without a clue would have done what Allen tried to do.

Allen’s amendment is probably dead. Hopefully Barto’ s bill is not.