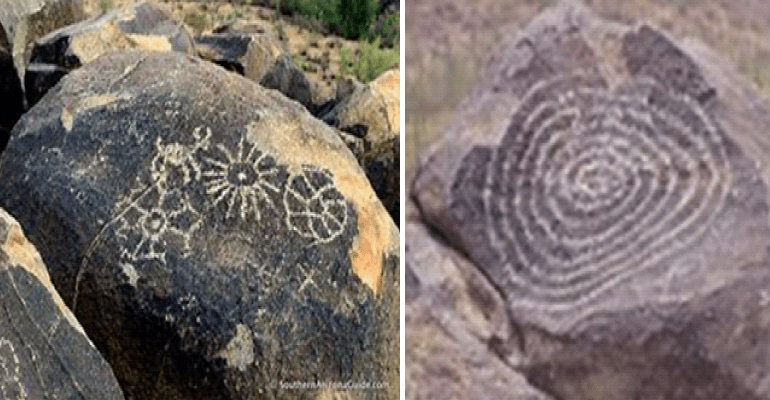

Rock art, made by native people hundreds and thousands of years ago, fall into two categories: petroglyphs, which are pecked or carved into the rock faces, and pictographs, paintings on the rocks. Most in our area are petroglyphs, and archaeologists still argue over what they are and what they may mean. One thing is for sure – they are not graffiti, not when it takes an inch per hour to create the images that have lasted so long.

The Avra Valley, now threatened by a new Interstate 11 highway, and surrounding mountains were home to the Huhugam, ancestors of today’s Tohono O’odham people. Archaeologists have corrupted the O’odham word to Hohokam. Those people farmed and hunted, built intricate canal systems to irrigate the desert, and probably came from the south to settle here, bringing Mesoamerican ball courts, plazas and platform mounds as part of their culture. They had governance and collective decision-making – it is no accident that villages were laid out along the Santa Cruz River 1-1/2 to 2 miles apart on opposite banks. It is likely that a prolonged drought forced changes in their way of life; huhugam means “all used up.”

Rock art is many things – spiritual connections to Creation, maps, recording of events, markers for special places, and more – and each may have more than one meaning or association. Many archaeologists are consciously no longer using the word “prehistoric” or “primitive” to describe ancient people, since they did have history which was passed on in song and story, and in rock art.

Two of the easiest places to view rock art are: Signal Hill, in Saguaro National Park (West), and in the wash below the Redemptorist Renewal Center. The Signal Hill picnic area is reached on the unpaved Bajada Loop Road off Sandario, and a ¼ mile down and up hike takes you to the top of the hill where plenty of rock art can be viewed. Please stay on the marked trail and do not touch the petroglyphs. Park fees should be paid at the Red Hills Visitor Center.

Signal Hill ‘glyphs include bighorn sheep, and representations of a flower-based spirituality that came up from southern Mexico. Signal Hill was likely a gathering place for religious rituals. Spiral solstice and equinox markers were the seasonal calendar necessary for agricultural people; on the day the seasons shifted a shadow cast by another carefully-placed rock would split the spiral directly down the center.

On Picture Rocks Road, just west of the Redemptorist Center and before crossing the Tucson Mountains at Contzen Pass, there is an unpaved parking area on the south side and a trail into the wash where a collection of petroglyphs rises above it. Bighorn sheep, deer, solstice markers, and linked dancers await you.

A common motif in the Sonoran Desert are stick figures with a long middle “leg.” Male archaeologists have called it “male bragging,” but then there are similar figures with large bellies. So, pregnant men? Or could these be the recording of births, which could explain why they are so widespread and clearly not the work of any one individual. If so, then that is a form of written history. (L. near Cocoroque Butte; R. Signal Hill)

Remember: Stay on the trails and take nothing but photographs and memories, leave nothing but footprints. Touching petroglyphs leaves skin oils that degrade the rock. These have existed for hundreds and thousands of years, and should be left intact for future generations to marvel at.