WASHINGTON – When tenants of a student housing complex poured beer and tossed cans from a balcony onto children playing in the Islamic Center of Tucson’s parking lot last month, Councilman Steve Kozachik saw a hate crime.

“This is not an example of a drunken prank,” Kozachik wrote in an angry email to managers of the Sol y Luna apartments. “It is nothing less than a hate crime.”

Irfan Sheikh is not so sure.

“We do not want to make it like it’s a huge faith-related issue,” said Sheikh, who is chairman of the ICT board. “We realize it’s a couple of kids. It doesn’t represent the community.”

It’s not as if Sheikh is a stranger to faith-based hate: In 2016, a fire was lit in a recycling bin outside the mosque during morning prayers, and a year later someone vandalized the mosque after hours, breaking into the building and destroying numerous Qurans.

But the Aug. 24 beer-can incident falls into a separate category for Sheikh – just another example of youthful rowdiness and intoxication that leads to misconduct by the mosque’s neighbors.

For Imraan Siddiqi, executive director of the Council on American-Islamic Relations-Arizona, it’s the difference between a hate crime and what he says might be better labeled a “hate incident.”

“Hate crime is a pretty severe term to be used,” Siddiqi said. But he agrees with Kozachik that the history of behavior against ICT cannot be overlooked.

“This mosque has endured an almost endless stream of incidents targeting this population in different ways,” he said.

That behavior began when students first moved into the apartments next door. Four University of Arizona students were evicted in 2016 after throwing glass bottles and cans into the ICT parking lot. Another incident occurred earlier this year when a stick tossed from an apartment balcony resulted in a shattered car window.

After those incidents, GMH Capital Partners, the group managing the apartment complex, installed surveillance cameras and tightened the lease agreement to spell out penalties, including eviction.

GMH Vice President of Operations Justin Wybenga said in a prepared statement after the latest incident that the apartments maintain “a zero-tolerance policy when it comes to our residents endangering the safety of our fellow community members.”

“If the investigation determines a Sol y Luna resident is responsible for the incident, their lease will be terminated effective immediately and the conduct violation will be reported to university officials as appropriate, per our lease agreement,” his statement said.

Mosque officials have been working with the Tucson Police Department on the beer-can incident and the department has assigned a detective to the case, who is looking at it for now as an issue between neighbors. Kozachik said that, through close work with the police and apartment administrators, the students in the latest incident were identified and told they will be evicted.

Sheikh said his top priority is safety of congregants and their children. He said that, while religion might act as a trigger, many of the incidents directed at the mosque are a result of “kids not realizing what they’re doing.”

“Students are there to learn,” Sheikh said. “They don’t buy into bigotry.”

Abdul Aziz, the secretary of outreach for the Ahmadiyaa Muslim Community in Tucson, agrees that the students’ behavior is often rooted in mischief, not Islamophobia.

“Tucson is a wonderful community and it has not done anything anti-Islamic except those students who are just making merry,” he said.

But others point to a history of incidents that they say are not so playful.

Maria Molina, ICT’s head of public relations, said in a press release after the last incident that there have been times when children at the mosque had to endure “racist remarks and obscenities” from drunken passersby and tenants.

Kozachik cited other instances when apartment residents were even more brazen.

“Ethnic epithets were being yelled out and people were hanging Israeli flags,” he said. “It was clearly directed at Muslims because they were Muslims.”

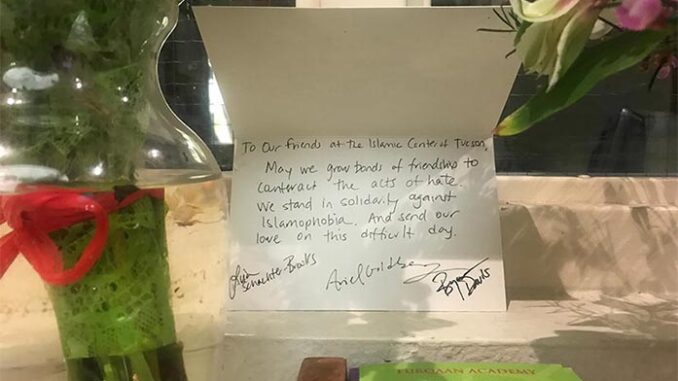

Siddiqi said CAIR-AZ has worked with ICT over the course of these incidents. He said that while members express frustration, they refuse to engage in any escalation, more concerned with maintaining their position as a “pillar” in the community.

But that doesn’t mean there’s not a problem, he said.

“If you see something along these lines happening to a community over and over again, there’s obviously some bias on display here,” Siddiqi said. “Is this a common experience amongst houses of worship that are adjacent to these large buildings? Or is this something that is unique, happening to only Muslims?”

Calls to a dozen churches around the University of Arizona campus turned up only one remotely similar incident, at the First United Methodist Church, where someone painted an upside-down cross on the church last year.

A staffer at Trinity Presbyterian Church noted past issues with after-hours drinking in the parking lot, but said security measures remedied the situation.

Kozachik said he is not surprised that Muslim community leaders balk at using charged language.

“They’re a group that is targeted for who they are all over this country,” he said. “They don’t want to draw attention to themselves.”

Sheikh said attention can sometimes backfire, as it did after the latest incident.

“When the news aired the same night, later that night, somebody from another building threw a bottle at our gate of the parking lot,” he said. “So that’s another problem: You talk about it, then you invite more trouble.”

Sheikh said there have been other troubles since the August incident, but the mosque decided against reporting them.

Aziz said he wishes Kozachik would try a different approach.

“If he’s interested in bringing peace to the community, he can tell them, ‘Folks, to me, it looks like a hate crime, which we should not engage in. But your Muslim neighbors don’t think it is a hate crime,’” Aziz said. “‘All they want is respect for you and they expect respect from you.’”

As long as the apartments and their open balconies are there, Sheikh and Kozachik believe there will continue to be problems. For now, Sheikh fears for the well-being of his community members. He worries that one day, a falling object might kill someone.

“I just don’t understand how to stop it,” Sheikh said.

He does know more dialogue is needed.

The ICT is considering installing signs with friendly messages outside the mosque, and Sheikh wants to hold a joint ice cream party in the near future to introduce apartment residents to congregants.

He wants that dialogue to include the students from the Aug. 24 incident, too.

“I don’t want them to be expelled,” he said. “I wanted to go and talk to them. I don’t want these students evicted.”