The Hub claim was staked by William Tuttle on March 29, 1875 and the Irene claim was staked by Irene Vail of Globe on September 1, 1876. These mining claims became the nucleus of the Silver Queen mine that later became the Magma mine. Phillip Swain organized the Silver Queen Mining Company in 1880 to develop silver-bearing vein that cropped out at the site.

Mining activities in the Silver Queen area were initially served by the community of Queen, which was renamed Hastings in 1882. By 1882, early development of this property included a 400-foot vertical shaft that had short cross-cuts to the vein on the 100, 200, 300 and 400-foot levels. However, only limited amounts of silver ore were encountered in these underground workings. The Irene claim was patented on October 31, 1885, while the Hub claim was patented on November 3, 1886. Operations were suspended at the Silver Queen mine in 1893, when declining silver prices made the project unprofitable.

George Andrus examined the Silver Queen’s copper resource in 1906. Encouraged by its potential, he formed the Queen Copper Mining Company. However, a 35% decline in the price of copper due to the Financial Panic of 1907 resulted in the abandonment of this early effort to develop the copper resources at this site.

William Boyce Thompson organized the Inspiration Copper Company (a predecessor of Inspiration Consolidated Copper Company) in the Miami area in December 1908. He subsequently sold his interest in that company in September 1909.

Looking for new opportunities, he sent his field engineer, Fred Flindt to examine the Daggs group of claims south of Inspiration Consolidated Copper Company in Superior mining district. While there, strong faulting along the Silver Queen vein attracted Flindt’s attention and he acquired an option on the property for his principals. Based on Flindt’s recommendation, mining engineer, Henry Krumb was asked to make a detailed examination of the Silver Queen mine. Encouraged by Krumb’s favorable report of March 6, 1910, Thompson and George Gunn purchased the Silver Queen mine for $130,000 and incorporated the Magma Copper Company in May 1910. Thompson renamed his new mine, Magma.

Upon acquiring the property, Magma Copper Company set about exploring its holdings. By mid-1911, the Silver Queen shaft (now known as the Magma No. 1 shaft) was deepened from 400 to 650 feet and the Flindt tunnel driven from the surface to the 215-foot level of the shaft.

By 1912, the Magma No. 1 shaft had been deepened to 800 feet with developmental crosscuts driven on the 500, 600 and 800-foot levels being actively mined. During early development of the Magma property, supplies were brought to the site by wagon from the Phoenix and Eastern railhead near Florence, while direct smelting ores were hauled to the railhead on the return trip for shipment to ASARCO’s newly commissioned smelter at Hayden, Arizona.

While developing the property, small, irregular, rich copper-bearing zones that had been encountered at shallow levels became more continuous with depth. This resulted in an increased pace of mine development and erection of a 200-ton per day concentrator, which was placed on line in April 1914. This facility employed Wilfley gravity tables and Callow flotation cells to produce a concentrate product that was suitable for smelting. A 2,600-foot aerial tramway was constructed from the portal of the Flindt tunnel to the new mill site. Other improvements included a 15-mile power line, linking Superior with the Miami area, where it connected with a government-owned power line from the Roosevelt dam on the Salt River.

It was recognized very early that profitable production of copper ores at the Magma mine would be dependent on reliable, cost-efficient transportation to ship products to and from the Superior mining camp. This resulted in the incorporation of Magma Arizona Railroad in October 1914. A thirty-one mile, 36-inch narrow gauge rail line connecting Superior with the Phoenix and Eastern Railroad at Magma Junction near Florence was completed in May 1915 at a cost of $160,000. This significantly lowered the cost of shipping timber, machinery and all sorts of other goods required to support Magma Copper’s operation and the town of Superior as well as outbound shipments of copper concentrates to the Hayden smelter.

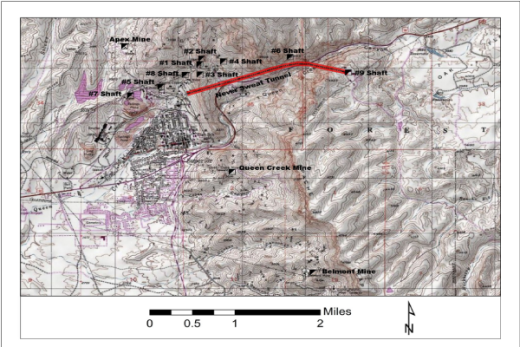

Located 400 feet north of the No. 1 shaft, the No. 2 shaft was sunk from the 215-foot level of the Flindt tunnel in 1915, reaching the 1,500-foot level in 1916, where it encountered the Magma Vein. Mineralized from wall to wall at that point, this high-grade zone was 34-feet thick and averaged 10.52% copper, 5.37 oz/ton silver and 1.26 oz/ton gold. As a result of this discovery and the increased demand from the war in Europe, Magma Copper increased the capacity of its concentrator to 300 tons/day.

The discovery of a major ore body on the 1,500-foot level began to tax the hoisting capacity of the No. 2 shaft. By the time the No. 2 shaft had been deepened to the 1,800-foot level in 1917, mine officials decided the hoisting capacity needed to be expanded. Located about 400 feet south of the No. 1 shaft, the No. 3 shaft was collared in late 1917. A 600-kw power transmission line from Goldfield was added in 1918 to supplement the Miami line.

Despite falling copper prices following the end of World War I in November 1918, Magma Copper completed sinking the No. 2 and No. 3 shafts to the 2,000-foot level in 1919. They also drove the Main Tunnel (500-foot level) from the surface to both of these shafts, significantly reducing the cost of hoisting the ore to the Flindt Tunnel. The No. 4 shaft was collared east of the existing workings in 1920 for use as an exhaust shaft in an effort to improve the ventilation within the hot underground workings.

By 1921, copper prices had fallen to 14.7 cents/lb of copper. In response to the decreased demand Magma Copper temporarily suspended ore production in March of that year. However, they continued development work, completing the No. 2 Shaft to a depth of 2,450 feet. Encouraged by the presence of high grade ore at this depth, Magma Copper sought ways to reduce its operating costs. Results of a feasibility study showed that in-house smelting and a standard gauge rail line would reduce the operating costs by 2 cents/lb of copper recovered.

Having decided to proceed with this expansion project, Magma Copper issued $3.6 million in bonds to finance its construction in early 1922. The rail line was converted to standard gauge during the spring of 1922. The concentrator remained closed during 1922 and its capacity was expanded to 600 tons/day. Work on the smelter commenced in December 1922 and limited milling of ore resumed during 1923. Magma Copper’s new smelter was commissioned on March 29, 1924 at a total cost of about $1.9 million; allowing the mine to resume full operations. The efficiency of the operation was increased by this expansion program, allowing it to lower its production costs to 7.51 cents/lb of copper recovered. Magma Copper became the first mining company in Arizona to offer life insurance to its employees in 1925.

Further improvements to infrastructure included replacement of the aerial tramway with a surface rail system that connected the Main Level portal of the mine with the mill in 1926. Located about 2,400 feet southwest of the No. 3 shaft, the vertical No. 5 shaft was collared in 1926 and discovered the West ore body at a depth of 2,150 feet in 1927.

Superior Smelter (August 2009)

Superior Smelter (August 2009)

The West ore body of the Magma vein is located between the north trending Main Fault and the northwest striking Concentrator Fault in the western portion of the mine. The bulk of the ores within the Main and Central ore bodies of the Magma vein are confined to the eastern footwall of the Main Fault.

A deadly fire in the No. 2 shaft of the Magma mine claimed the lives of seven miners on November 24, 1927. A second fire broke out in the No. 1 shaft on November 27, 1927. Both shafts were heavily damaged by these fires. The No. 1 shaft was abandoned after it caved in after the fire. However, the No. 2 shaft was repaired and placed back into service in 1928.

With the development of the No. 5 shaft, which reached the 2,960-foot level in 1928, the large new area in the western portion of the mining operation was beginning to tax the capacity of its ventilation system. To solve this problem the No. 6 shaft was sunk 4,500 feet east of the No. 3 shaft in early 1929, improving air flow in the eastern portion of the mine. The No. 7 shaft was collared approximately 500 feet west of the concentrator later that year. This significantly improved the ventilation in the western portion of Magma’s underground workings.

With the crash of the stock market in October 1929, the price of copper fell from 18.2 cents/lb. in 1929 to a low of 6.15 cents/lb. in 1932. In response to the declining price of copper, Magma Copper cut production in the fall of 1930. Reduced production schedules continued until 1936, when conditions improved. With the price of copper reaching 12.04 cents/lb in 1937, Magma Copper began plans to develop the west ore body, which had been discovered a decade earlier. However, continued expansion of the operation required finding a solution to the high temperatures that were encountered in the deeper levels of the mine.

As Magma Copper’s operation reached greater depths, temperatures of the rock continued to increase. By the early 1930s, the No. 5 shaft had reached a depth of 3,200 feet, where the rock temperatures exceeded 126 degrees F. Under these conditions, it required several years of ventilation to reduce the temperature in the underground workings to a point allowing safe working conditions for the miners. Willis H. Carrier installed air conditioning units in the lowest working levels (3,400 and 3,600-feet) of the operation in July 1937, significantly lowering temperatures. This innovation was supplemented by the construction of a regenerative cooling tower at the surface in 1947.

The No. 8 shaft was collared between the No. 5 and No. 3 shafts in 1935 and natural gas replaced fuel oil at the smelter in January 1936. Other improvements included the addition of a 250-stpd capacity zinc flotation circuit at the concentrator in 1937. Mining methods at this time employed a system of square-set timbered stopes that were backfilled with mine waste. In January 1940, workers on the 4,000-foot level discovered the Koerner vein further extending the life of the operation.

With the prospects of war looming during the late 1930s, production steadily increased, but Magma Copper continued to operate with a summer shutdown through 1941 due to the erratic price of copper, which fluctuated between 10 and 12 cents per pound. With America’s entrance into the war in December 1941, Magma Copper operated at full capacity throughout the war. However, the military draft and competition from defense plants made it necessary to train inexperienced help to achieve Magma Copper’s wartime production goals. Recovery of a zinc by-product was discontinued in July 1945.

As World War II came to a close, Magma Copper’s original concentrator was nearing the end of its productive life. It was replaced by a new 1,500-ton per day facility in 1946. While attempting to locate an offset portion of the Magma vein east of a north trending fault zone, underground exploration drilling below the 2,550-foot level in the east end of the mine encountered manto-style replacement ores near the base of the Devonian Martin Formation in 1948. This zone became the “A bed” ore body.

Unlike the steeply dipping, east-striking Magma vein, which cuts across the lower portion of the east-dipping Precambrian and Paleozoic stratigraphic section in the central and western portions of the mine, the large, conformable, manto-style ore bodies of the “A bed” are characterized by a chalcopyrite-bornite-hematite-quartz-calcite assemblage that preferentially replaces a favorable dolostone bed near the base of the Devonian Martin Formation, which strikes north and dips about 30 degrees to the east. The manto ores form irregular tongue-like bodies that measure up to 900 feet along strike and extend up to 4,400 feet down dip.

Recovery of zinc from copper-zinc vein ores above the 2,250-foot level briefly resumed in July 1950 due to increased demand that resulted from the onset of the Korean War. Production of zinc was suspended in August 1952 with the depletion of its remaining copper-zinc reserves. Production of replacement ores from the newly discovered “A” bed commenced in 1953, while extraction of ores from the Koerner vein ceased in 1957. As production was phased out in the western and central portions of the Magma mining operation, replacement ores in the eastern portion of the mine were developed and brought on line, using both square-set and undercut-and-fill mining methods. Mining of the Magma vein in the western portion of the mine that was accessed by the No. 5 shaft ceased in 1961. Mining of the Magma vein in the central portion of the mine ceased in 1966.

During the late 1950s and early 1960s, the Magma Copper Company consolidated mining properties in the Superior mining district, purchasing the Magma Apex Copper Company in August 1957, the Queen Creek Copper Company in June 1958 and the Belmont Mining Company in April 1961.

Four additional manto-style, replacement ore bodies (known as the B, C, D and E beds) were discovered in 1965. The “B bed” is hosted by carbonate horizons near the top of Devonian Martin Formation, which is marked by a thinly laminated limestone, locally known as the “Last Black Shale.” The “C bed” is hosted by a limestone horizon located about 30 feet above the base of Escabrosa Limestone, while the “D bed” is located at the top of that unit. The “E bed” is hosted by the first carbonate horizon above the maroon shale at the base of the Pennsylvanian-Permian Naco Group.

The Newmont Mining Corporation, which had been founded by William Boyce Thompson in 1916, increased its equity interest in the Magma Copper Company from 21.5% to 80.6% in May 1962. Newmont then acquired the remaining of stock in May 1969, making Magma Copper a wholly-owned subsidiary.

The high costs of developing and mining the replacement ores in the eastern area of the Magma mine resulted in the decision to expand the operation’s infrastructure in an effort to reduce production costs. This four-year expansion program began in 1969. It included an increase in the concentrator’s capacity from 1,500 to 3,300 tons per day in 1971, construction of the east plant site, the sinking of the 4,843-foot, Magma No. 9 shaft, and driving the 9,700-foot Never Sweat Tunnel on the 500-foot level from the west plant site to the No. 9 shaft. This project was completed in August 1973 at an estimated cost of $74.8 million.

Entrance to “Never Sweat Tunnel” with ventilation system (June 2015)

Entrance to “Never Sweat Tunnel” with ventilation system (June 2015)

As a part of these cost reduction measures, a decision was made to close the Superior smelter. Following its closure in July 1971, copper concentrates from the Magma operation were shipped to Newmont’s larger smelter at San Manuel, Arizona.

After 71 years of production the Magma Copper Company ceased mining and milling operations at its Superior operation in August 1982 due to high operating costs and declining copper prices, which fell to 73 cents/lb in 1982. The underground mine workings were allowed to flood to the 3,000-foot level after care and maintenance operations were suspended at the site in 1985.

In March 1987, Newmont Mining Corporation combined the assets of its wholly-owned, Arizona copper subsidiaries into a new public company, and spun-off a new Magma Copper Company, distributing Magma’s equity to Newmont shareholders. Magma Copper became a company in which Newmont owned 15% of its common shares. It was a stand-alone copper company under new management.

With the rising copper prices during the late 1980s, the new Magma Copper Company re-evaluated its operation at Superior and determined the recent increase in the price of copper had transformed approximately 4.4 million tons in the resource at its closure in 1982 into a mineable reserve. They commenced dewatering the Magma mine in late 1989, lowering the water level to the 3,600-foot level by July 1990. Commercial operations resumed in September 1990. However, mining operations were temporarily halted by a fire in November 1991.

Broken Hill Proprietary Company Ltd. (BHP) acquired the Superior operation through its merger with the Magma Copper Company in January 1996, forming wholly-owned subsidiary BHP Copper, Inc. All operations at Superior were suspended on June 28, 1996 after depleting its remaining mineable reserves.

Over the 86-year life of Magma Copper’s Superior project (1911-1996) approximately 27.6 million short tons of ore averaging about 4.9% copper were mined, recovering 1,299,718 short tons of copper, 36,550 short tons of zinc, approximately 686,000 ounces of gold and 34.3 million ounces of silver.

Copyright © (2015) by David F. Briggs. Reprint is permitted only if the credit of authorship is provided and linked back to the source.