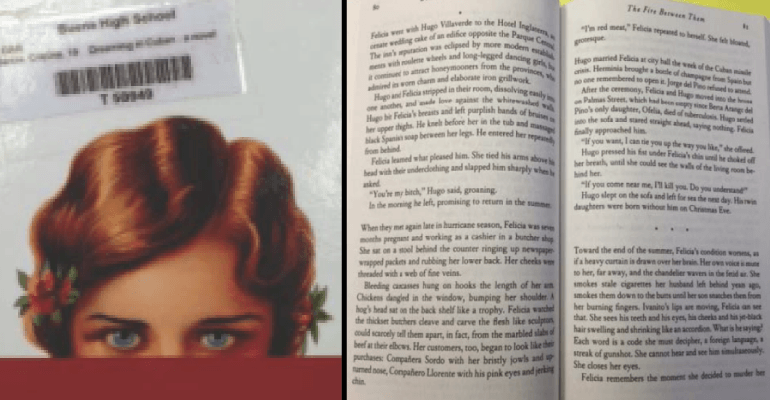

The sexually explicit novel “Dreaming in Cuban” may be considered recommended reading for high school sophomores by Common Core proponents, however Sierra Vista Unified school administrators have decided to pull it from its approved reading list, according to the Daily Caller.

The administrators’ decision was spurred by parents and community members who were upset the novel had been assigned to students in two Buena High School English classes. According to one parent, students were asked to read portions of the novel out loud in class, according to the Caller.

According to sources at the Arizona Department of Education, the book was on a suggested text list for teachers, it had not been approved by the governing board for students. Teachers might use portions of the text to show diversity, in the instance of “Dreaming in Cuban” the teacher might read the portion in which the main character has a positive experience dreaming in the Spanish language. The book was on the suggested reading for 11th grade teachers, not 10th graders.

Whatever the case may be, Arizona Superintendent of Public Instruction John Huppenthal reminded Arizona superintendents and governing board members today, that it is their responsibility to know what students are reading in class. In a letter dated today September 13, Huppenthal advised the group, “ As with all curriculum materials, it is the responsibility of the local LEA to carefully review items to ensure they are appropriate for learners. Local decisions made on instructional materials must be made with caution and sound professional judgment. It is an expectation that local school boards, administrators and teachers review instructional materials, including reading passages, prior to them being assigned to students.”

Huppenthal continued, “ As you begin to make decisions about aligned instructional materials, I remind you of the importance of choosing materials that are appropriate for your students and community.”

Huppenthal included in his letter a memorandum entitled “Local Curriculum Decisions Regarding State Board Adopted Standards.” It reads:

In Arizona, the state board of education has the responsibility to adopt educational standards as per state statute. Arizona’s state law establishes the State Board of Education’s responsibility in defining and adopting K-12 academic standards A.R.S. 15- 203. The state standards outline by grade level what students must know and be able to do, while local curriculum defines how the standards will be taught and with what instructional materials. State law also identifies the responsibility of local school boards to adopt curriculum and instructional materials that are responsive to the local students as stipulated in A.R.S. 15-721 and A.R.S. 15-722. According to A.R.S. 15-721 (A) the governing board shall approve for common schools the course of study, the basic textbook for each course and units recommended for credit under each general subject title prior to implementation of the course…and (B) if any course does not include a basic textbook, the governing board shall approve all supplemental books…

A.R.S. 15-721 reflects the critical importance of local decisions regarding instructional materials to ensure that:

• all students’ learning needs are successfully met;

• all students have access to relevant, meaningful material;

• local systems remain flexible in responding to the diversity of the families and students that they serve while ensuring high student achievement in the state’s academic standards.

Curricular decisions must be thoroughly vetted at the local level to ensure appropriate, sufficient and rigorous content for all learners.

As an example and separate from the adopted state standards for English Language Arts are three supplemental informational documents for teachers. Appendix A provides research supporting key elements of the standards and a glossary of key terms. Appendix C provides annotated samples of student writing. Appendix B serves to help educators understand varying degrees of text complexity to support professional decisions regarding the local selection of appropriate texts of similar complexity. It provides a table of contents and excerpts of sample texts illustrating the density, structure and complexity of texts at specific grade bands. As local educators engage in the process of selecting instructional materials to support local curriculum decisions, Appendix B provides a tool to gauge the complexity levels of text being considered for use. Measuring text complexity is a three-part model based on qualitative and quantitative indices of inherent text difficulty balanced with educators’ professional judgment in matching readers and texts in light of particular tasks. While this resource was created by a broad range of literary experts across the country, it remains critically important that decisions regarding text should be made at the local level. Using the table of contents and/or samples of texts within Appendix B as a reading list is an inappropriate use of the resource.

It’s important to note that while textbooks and instructional support materials are a component of a district’s or charter’s adopted curriculum these resources alone do not constitute a comprehensive curriculum. Curriculum is essentially the organized preparation and plan of how the academic state standards will be taught. In Arizona, decisions regarding curriculum are the purview of local school boards and local education agencies. Curriculum is supposed to be a carefully constructed program or blueprint of learning that builds a plan for effective teaching and learning from the expectations set in the academic standards. A comprehensive curriculum must be approved and adopted at the local level as stated in A.R.S. 15-721 and 15-722 and includes:

• a complete scope and sequence that defines the breadth and depth of the content that will be studied

• a pacing guide that maps the intended content across the time identified for learning

• guidance on effective instructional strategies that support learning

• identification of approved and adopted instructional materials and resources

• an assessment plan that clearly articulates how student learning will be measured and the expectations for student performance that will demonstrate mastery of the content

The responsibility and authority to develop a local curriculum resides with the local education agency and the local school board.

Two years ago, members of TU4SD and other activists tried to pass legislation that would have required publically funded schools to publish their curricula along with required reading and supplemental materials online. The Bill Ayers backed group, AERA, joined the Arizona Education Association and the Arizona School Board Association (ASBA) to stop the legislation. The ASBA argued that it would be too onerous for districts. The AERA argued that it would “chill” teachers’ ability to introduce materials at will, including periodicals and new films.

Former State senator Rich Crandall, currently the head of the Wyoming Department of Education, was instrumental in preventing the proposed legislation from getting out of committee onto the floor for a vote by the Senate.

As a result of “curriculum dumping” few governing board members ever specifically review any reading materials before they approve it. The practice of “curriculum dumping” is widely practiced around the country.

The Tucson Unified School District was found to have violated state law in 2011, when it discovered that the District’s governing board had not reviewed and approved materials used in the district including it’s Mexican American Studies classes. The District lost their appeal of that decision.

In a separate, but related case, in 2012, federal Judge Wallace Tashima ruled in the Tucson Unified School District’s Mexican American Studies class case, that teachers in Arizona do not have a right to free speech in K-12 classrooms. Tashima found that teachers must adhere to governing board approved materials.

To read an excerpt from the controversial book click here.