If you like to hike in the foothills of the Santa Catalina Mountains, you can enhance your excursion by learning some geology along the way.

The Arizona Geological Survey (AZGS) has A Guide to the Geology of Catalina State Park and the western Santa Catalina Mountains as a free, downloadable, 57-page book. This is part of the AZGS “Down-to-Earth” series. The guide contains six maps, 21 geologic features and 30+ photographs and illustrations that describe and illustrate the geology and geologic setting of Catalina State Park.

The Arizona Geological Survey (AZGS) has A Guide to the Geology of Catalina State Park and the western Santa Catalina Mountains as a free, downloadable, 57-page book. This is part of the AZGS “Down-to-Earth” series. The guide contains six maps, 21 geologic features and 30+ photographs and illustrations that describe and illustrate the geology and geologic setting of Catalina State Park.

This book is written for the visitor who has an interest in geology, but may not have had formal training in the subject. It may also help ensure that the visiting geologist does not overlook some of the features described.

“The purpose of the field guide is to provide the reader with an understanding of the dynamic processes that have shaped this exceptional landscape. Many of the features discussed in the text will be encountered again and again as you continue to explore the Southwest. We hope that your experience at Catalina State Park and the Coronado National Forest will enhance the pleasure of those explorations.”

The value of this guide is that you learn about what may look to the untrained eye like unremarkable features, maybe just a pile of rocks, but each feature has a story that bears on the geology of the region and provides you with a better appreciation of geological forces that shape our land.

Here are two examples from the publication:

Feature 3: Debris-flow rafted boulders

Large boulders, 6 to 30 feet in size and weighing 50 to 1000 tons, make up the surface of these old alluvial fan remnants. The boulders are blocks of granite and gneiss derived from the west face of Pusch Ridge, one-half mile to the east.

The alluvial fan surface on which you are standing once extended to the base of Pusch Ridge. These huge boulders fell from the cliff face (perhaps during earthquakes), accumulated in drainages at the heads of the old alluvial fans, and were rafted to their present location along the lower fan slopes by debris flows. Subsequent erosion by running water has washed away most of the old alluvial fan material, separating these remnants from the cliff face that was the source of the boulders.

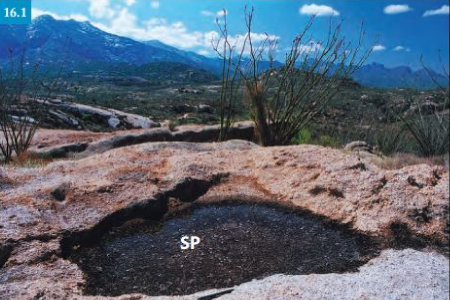

Feature 16: Solution pans

Many relatively level granite surfaces in this area contain flat-bottomed, circular depressions that commonly have overhanging sidewalls. These solution pans or gnammas (Scrabble player alert), which are up to 3 feet across and 4 inches deep, can hold water for days after rain and snowmelt.

Pans form at points of rock weakness (joints, areas of lichen disintegration, or flaked surfaces) and expand by chemical and lichen-induced weathering. Periodic pooling of water results in the chemical alteration of the minerals in the nearby rock. Some minerals dissolve, some oxidize, and others are changed to clay minerals. Lichens and algae flourish in the more humid environments of the pans and decompose the granite grain by grain. The rock disintegrates slowly and the resulting debris is swept and flushed from the enlarging solution pans by wind and heavy rains.

Download and look over this free publication. It will give you a new appreciation of the place we live in. See also my article The Gold of Cañada del Oro. Cañada del Oro runs through the park.

Note to readers: I have constructed a linked index to more than 400 of my ADI articles. You can see it at: https://wryheat.wordpress.com/adi-index/

You can read my comprehensive, 28-page essay on climate change here: http://wp.me/P3SUNp-1bq