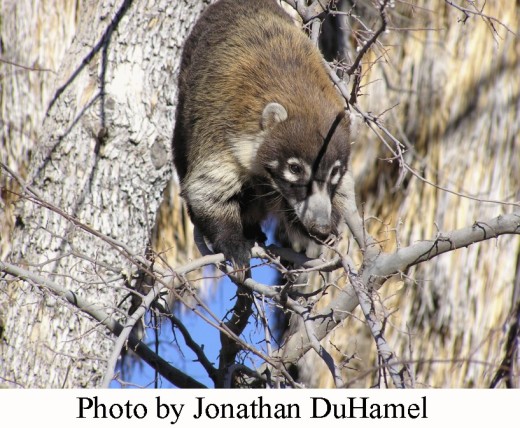

The coati (males are called coatimundi) is a racoon-like animal with a long tail and long snout. It ranges from Columbia, through Central America into Mexico, southern Texas, New Mexico, and southern Arizona. The subspecies in the U.S. is called the white-nosed coati, Nasua narica, but there seems to be controversy over the taxonomy and the number of species.

Coatis have reddish-brown to chocolate-colored fur with gold highlights. They have a white snout and sometimes white on the breast. The two-foot long tail often has light and dark bands which become more prominent with age. Coatis grow 30- to 55 inches long and stand 8- to 12 inches at the shoulder. Females usually weigh about 10 pounds, and males can weigh up to 25 pounds.

Coatis inhabit scrub-oak woodlands and riparian areas. They make nests in caves or platforms in trees. Coatis are relative newcomers to Arizona. They were first reported in Arizona in 1892 and seem to be expanding their range.

Coatis are opportunistic omnivores, feeding mainly on fruits, invertebrates, and small vertebrates. They have strong, curved digging claws on the front feet which they use to tear up logs and dig in the soil. They use the front feet and claws to roll small prey in the dirt prior to biting off the head. Coatis have a keen sense of smell and a nose that is used much like a pig’s for rooting out insects, lizards, and tubers. In Arizona, they will eat acorns, cactus fruit, manzanita berries, pinon nuts, wild grapes, stalks and seeds of agave, a variety of roots and grains, insects, arachnids, mice, pack rats, snakes, lizards, carrion, bird eggs, squirrels, and even skunks.

Coatis are very social animals. They tend to travel in large bands, mainly females and the young. The bands commonly contain 25 to 30 individuals and bands of 75 have been reported. Mature males are solitary except during mating season (April). The mated females give birth to 4- to 7 pups in July.

I’ve seen many Coatis in the Chiricahua Mountains. I’ve also experienced a particular defensive tactic they have. If they feel threatened, they will all climb a tree and send a rain of feces down on the perceived threat.

Coatis use their long tail for balance and communication. The tail is usually held up communicating safety and contentment. The tail is down to signal danger. Coatis also use a variety of vocalizations. According to the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum, coati communication includes the following:

- The contact call: a rapid series of high-pitched, low intensity chittering sounds used when members of the tribe become separated.

- Grooming: an activity that helps strengthen social bonds.

- Contact/chase: Females chase and threaten males during the spring. This threat is used during the summer against other females if they approach cubs too closely. In the fall and winter, this activity is friendly play.

- Nose Up: The nose-up posture is used during an antagonistic encounter, often accompanied by baring the teeth, with the neck extended and the tail held straight out behind.

- Lunge: This may follow the nose-up along with biting if the other coati does not retreat.

- Chittering: A rapid series of short, high-pitched, bird-like sounds used by sub-adults as an offensive signal often followed by an unfriendly chase.

- Squealing can accompany antagonistic encounters and fighting.

So now that you know how to talk to coatis, go out to the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum to see them for yourself. They’re just hanging out waiting for you.

See more photos from the ASDM digital library here.

See my other natural history posts on ADI:

Thirteen venomous animals of the Southwestern desert

Pepsis wasps have the most painful sting

Nighthawks and Poorwills, birds of the night

Copyrighted by Jonathan DuHamel. Reprint is permitted provided that credit of authorship is provided and linked back to the source.