Review and Discussion

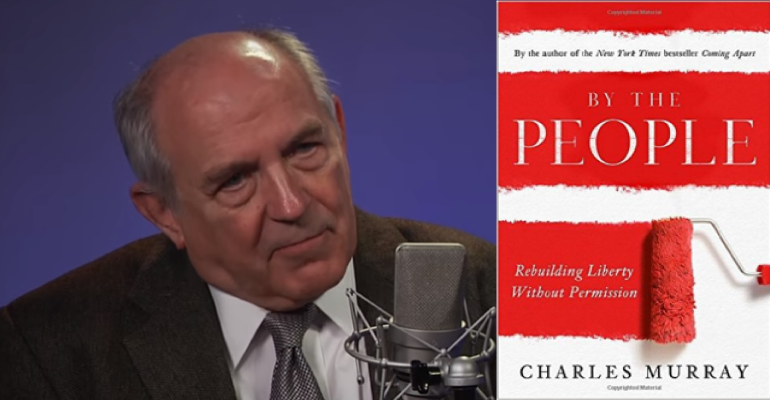

Charles Murray’s By The People argues that we must rebuild the federal government: it is out of control. Governmental malfeasance is so widespread that it can no longer be stopped at the ballot box. Honest and courageous politicians have been elected but extra constitutional practices in the House, Senate, and White House have become too widespread and common to be overcome by a few men and women of character, conviction, competence, and courage.

Murray begins by describing the history of court cases that show how the Constitution has been marginalized. He asserts that the legal system gradually became lawless as legal precedents were ignored, “repurposed,” or overturned. Really? Have we become a largely lawless nation, governed by unaccountable elites, often in judicial garb?

Is lawless too strong a term? Probably not, and for 3 reasons:

- Laws are strangling small business innovation. As business people can testify, moderate sized businesses must hire entire new human resources and legal staffs just to assure that a minimum number of legally binding regulations is broken. There is such a thicket of invasive and constraining law that business, cannot function lawfully even as they generate the tax revenue our government so craves.

- “Lawless” or at least “extra-legal” comes to mind when thinking about how laws actually get written. High school civics classes on how laws are made describe intentions, not the actual process. There are so many issues and so many lobbyists and so many experts that much goes wrong. Staffers, not legislators, write the laws and other staffers write the regulations that give the meaning to laws. The argument is laid out in in Schweizer’s book, Extortion. https://arizonadailyindependent.com/2016/03/23/book-review-how-politicians-extract-your-money-buy-votes-and-line-their-own-pockets/

- A careful analysis of actual legal decisions is made throughout Murray’s book. Read it or any other analysis of a major area of law and you might begin to agree with Murray that the net result is: Lawlessness.

Judges are often quite intelligent people. But judges are fallible human beings. Some have great “compassion for the little guy” and great “suspicions about greedy business people.” Yet other judges lean so far toward “respect for the rule of law” that one wonders how they think humans survived before there were hundreds of attorneys in the yellow pages

In a jury trial, jurors decide matters of fact (did Johnny take the apples?) whereas judges decide matters of law (were the apples taken unlawfully?) Citizens and legal experts working together! But where is the jury, the citizen, in an appellate court or Supreme Court case? In these highest courts, judges decide both matters of fact and matters of law. But what do judges know? Too few judges exhibit a passing knowledge of how real businesses and local governments actually operate. They are no more expert than you or I in matters of fact. They are more expert in matters of law, to be sure, but please understand something: matters of law are matters of opinion. When judges make decisions they write opinions to justify their decisions. The opinions are backed by the full weight and authority of government but they are, nonetheless, opinions.

Why have appellate courts? Because judges can get it wrong. That is why there are multiple judges on appeals courts. At the Supreme Court, a democracy of 9, a simple majority rules.

Has any court ever made a decision that was later overturned on legal grounds? Silly question. Were that not common there would be no need for appeals courts. Does an appeals court ever get the legal reasoning gotched up? Silly question. Why else is there a Supreme Court? Is the Supreme Court infallible? If so, why are so many decisions split 5-4 rather than 9-0? The 4 Supreme Court judges who write dissenting opinions do not think the court is infallible. The court is called Supreme because the legal arguments must end eventually. It is supreme in that sense and in no other sense.

According to the US Constitution, we-the-people rank higher than the House of Representatives, the Senate, the President, and, yes, higher than the Supreme Court. That is how it should be but, when a politician third in line for the Presidency responds “Are you serious? Are you serious?” when asked by a citizen about Constitutionality we might have a problem. Who hears the voice of We-The-People? It is a better voice than that of a king or queen but it is more difficult to hear.

Case law, whether we like it or not, is a “living” record. That doesn’t make the law lawless or the Constitution itself a living document but it can make interpreting it cumbersome and error prone. Thus, whether or not Murray is correct in saying that law, as practiced, has become lawless, there is no reasonable doubt: after a couple of centuries of electing thousands upon thousands of fallible human beings to city, state, and federal governments, after centuries of asking them to “make laws,” if after doing all that we have not created a mess it would be a miracle!

How do we work our way out of the governing mess we have created? Murray argues that “throw the bums out” is unlikely to work any better now than when the first patriot shouted it hundreds of years ago. Some people (not Murray) argue that we should convene another Constitutional Convention and “Fix the Constitution.” Maybe a balanced budget amendment would help or maybe term limits should be written in or maybe we should abandon the electoral college in favor of popular votes or maybe we should repeal the 17th Amendment and have Senators elected once again by State legislatures, or …

Other thoughtful people shudder at the very thought of a Constitutional Convention. Anyone who has read the Federalist Papers and a few of the most faithful historical accounts of the period knows just how dicey the original convention was. (Hillsdale College offers excellent courses about the Constitution, online and free: https://online.hillsdale.edu/ ) Opponents of a convention look around and fail to see a modern day George Washington or Thomas Jefferson or James Madison.

Some people (not Murray) place their faith in using the 10th Amendment carefully and often to reassert the rights of the states (said to be sovereign except in enumerated ways.) The good folks at the 10th Amendment Center http://tenthamendmentcenter.com/about/about-the-tenth-amendment/ lay out arguments for using the Constitutionally specified nullification process to limit federal overreach and return government closer to the people.

Murray argues, reluctantly, that we are past the time when normal measures will work. He argues for a time honored practice that has been used over and over again in the USA: Civil Disobedience. Civil disobedience, really? Really. (Disclosure: I know Murray slightly. He is not a flamethrower. Murray was a Peace Corps volunteer in Thailand, is an historian (Harvard, A.B. 1961) and political scientist (MIT, Ph.D. 1974) and W.H. Brady Scholar at the American Enterprise Institute.)

Murray does not argue for taking mindlessly to the streets. Murray’s argument is for a very mindful/thoughtful/careful form of civil disobedience akin to what the 10th Amendment Center advocates. (The Goldwater Institute in Phoenix does relevant work supporting state rights and individual freedom.) http://goldwaterinstitute.org/en/

Murray devotes Chapter 5 The Ground Rules for Civil Disobedience to ideas for ignoring large portions of laws and regulations. Who knows how many such rules are not already ignored, forgotten in dusty court houses and state houses throughout the land? Surely there are many laws for which nullification would do no harm and many laws for which nullification would be beneficial.

Murray recommends both principled and practical Ground Rules for selecting laws for nullification. He mentions the Bureau of Land Management or Fish and Wildlife as places to hunt for stupid rules. Another rich source is the mass of regulations restricting entry into professions or access to a specific job. I once had to go to court to get a license to practice psychology; the administrative law judge who decided in my favor asserted that the case should never have had to come before him; it was clearly bureaucratic overreach. It was protecting psychologists from low fees but protecting the public from what? Incompetent psychologists? No law can do that but a law can allow incompetent psychologists to hang a license of the wall. It works the same way in other professions.

Murray points out that licensing laws affect as many as one third of all jobs. Why are so many licenses required? Do such laws protect the public? Or were they passed at the behest of lobbyists to guard their sponsors’ ability to charge big bucks for mediocre services? Maybe attorneys should be licensed; maybe physicians; maybe accountants. Then there’s meat and poultry and OSHA and EPA inspectors. Does anyone need a license to protect the environment? You can probably do so without a license, but don’t bet on it; the EPA employs 1,096 attorneys! (If 1,096 federal attorneys stood on the head of a pin would you and I be the ones getting stuck?)

Maybe Murray is onto something.

He has other ideas for Ground Rules; I like his ideas much better than Saul Alinsky’s Rules for Radicals. But I must say I hate the message in By The People. Had I not read Schweizer’s excellent book I would not have considered civil disobedience as a tactic let alone as a centerpiece of a strategy for turning back a few thousand freedom stifling government regulations that are harming our economy and our freedom. The argument for statesmanlike civil disobedience is worth considering.

Given the fact that there are now so many laws that many are unknowingly broken each day by hundreds of thousands of law-abiding citizens, maybe breaking laws strategically has merit. Has lawmaking become so corrupt and laws so convoluted that deliberate lawbreaking is not only acceptable but also necessary? I hope not, yet Murray makes a case I can’t reject entirely.